Why ceasefire in Ukraine may not mean peace

- April 1, 2025

- Posted by: Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (Retd)

- Categories: Ukraine, US

By taking Ukraine’s NATO membership off the table, the US is trying to assuage one of Russia’s main concerns. But there’s much more at stake now

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (Retd)

Fundamental changes in a superpower’s outlook and its altered perception about any major geopolitical issue can have a profound effect in international relations where conflict resolution or initiation is involved. We are in a time when the world is eagerly looking towards an evolving order that would enable a winding down of confrontation and return of growth. The Trump administration’s geopolitical outlook signals such a fundamental change.

There is no doubt that the first of those conflicts whose winding down will trigger more positives for the world is the Ukraine war, now into its third year. There are situations competing for attention, such as the Gaza war and tensions in the Indo-Pacific, besides geo-economic issues. However, the US President has correctly focused on Ukraine first. West Asian affairs involving Gaza, Iran, Syria and Israel are parts of a larger legacy issue. The breakout of more violence in the region will no doubt have a telling effect. Yet, Ukraine’s war involves a former superpower—now a big power—in a region where nuclear weapons are ranged and 32 other countries are in an alliance.

At a recent meeting with NATO defence secretaries, the new US defence secretary Pete Hegseth stated that Ukraine cannot join NATO; this is in line with the Russian demand too. It reflects the current US administration’s stance on a fundamental issue that is a complete reversal from the previous administration’s stance. However, this position does not, in itself, resolve the conflict, as other critical issues such as territorial disputes and security guarantees remain unresolved. But this single belief about the inevitability of Ukraine’s membership in NATO is what led to the war in the first place. Now without this issue, what constitutes obstacles to peace needs examination.

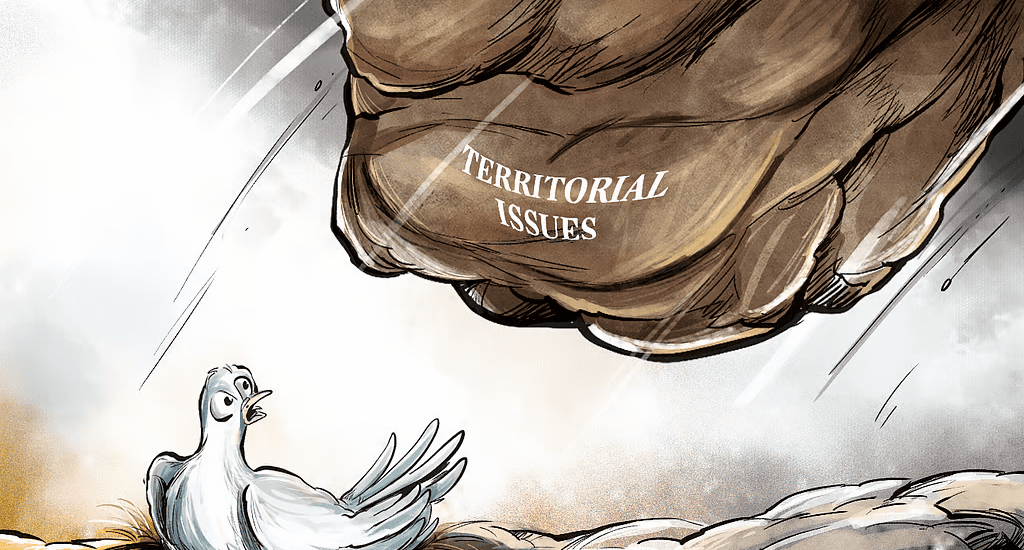

The first obstacle is that of territorial disputes and constitutional barriers. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and four additional Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson in 2022 has created a constitutional impasse, making any negotiations over their status exceedingly difficult. Ukraine’s constitution upholds its territorial integrity, leaving little room for a compromise without a legal transgression. The referendums held by Russia in those regions were widely condemned as illegitimate by Ukraine and the international community.

Advertisements

Ads end in 18

Of course, none of this comes in the way of a ceasefire, which can always be negotiated given the large-scale suffering and needless military pressure coming currently from the Russian side as a psychological message that Putin has the will and the means to continue the war.

The second barrier is about the divergent preconditions for negotiation. Russia demands that Ukraine cede control over the annexed regions and abandon its aspirations to join NATO. Conversely, Ukraine insists on the complete withdrawal of Russian forces from its territory and restoration of its pre-2014 borders. These mutually exclusive positions have led to a stalemate, with both sides unwilling to concede on these critical issues.

There is yet no certainty about the future of US-Europe security relations. As of March 9, the Trump administration had not explicitly called for NATO allies to cease all military assistance to Ukraine. However, the recent US policy shifts indicate a move toward reducing direct support for Ukraine and encouraging European nations to take on a more substantial role in providing aid.

The US recently ordered an indefinite pause on all US military aid to Ukraine, expressing dissatisfaction with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s commitment to peace negotiations with Russia. This suspension affects over $1 billion in arms and ammunition that were slated for delivery. Based on subsequent and more congenial communication with Zelenskyy, there is no doubt these will get released. But it is clear that Trump’s approach is radical and disruptive with an intent to send a strong message to all stakeholders and create grounds for US dominance at all subsequent meetings despite professing a ‘hands off Europe’ policy.

Advertisement

The first meeting between the US and Russia in Saudi Arabia faced much international criticism, which was unwarranted. As an administration seeking to establish peace in one of the tensest regions of the world, I suppose the US was right in listening to Russia to establish the terms for future talks and obtain greater clarity. The absence of Ukraine was appropriate, to the extent that these were not peace negotiations but just a fact-exchanging platform that may have gone awry with Ukraine’s presence.

The next round, with Ukraine present, will probably be a greater exercise in obtaining clarity and exploring avenues to resolve the conflict. It would discuss potential assurances for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. It may also address financial aid and reconstruction efforts for war-affected regions in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, the US’s change of approach has led to considerable turbulence in the European theatre. Instead of cowing down, a more agitated response appears to have emerged. German chancellor-in-waiting Friedrich Merz marked a moment of fundamental change in Europe’s defence strategy—he collaborated with the Social Democrats to revise fiscal policies, enabling substantial borrowing for defence and infrastructure. This step proves Germany’s commitment to enhancing its military capabilities and leading Europe’s defence initiatives.

French President Emmanuel Macron has proposed extending France’s nuclear deterrence to European partners, a move welcomed by nations like Poland and the Baltic states, but criticised by Russia. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen unveiled the ‘ReArm Europe’ plan, aiming to mobilise up to €800 billion to strengthen the EU’s military capabilities and reduce reliance on external allies.

The US is attempting to message Russia that NATO is no threat to it, but the European nations are showing little trust in either of them. As they bolster their defence capabilities, the trust deficit appears only increasing by the day. Can the US afford to detach itself from European security? A ceasefire is no guarantee that the next steps to peace will follow. Many a time, it just withers away. Peace in Ukraine appears yet a far cry.

(Views are personal)

(atahasnain@gmail.com)

Ata Hasnain | Former Commander, Srinagar-based 15 Corps; Chancellor, Central University of Kashmir