Uncertainty in Pakistan due to dynamic situation

- September 12, 2023

- Posted by: admin

- Category: Pakistan

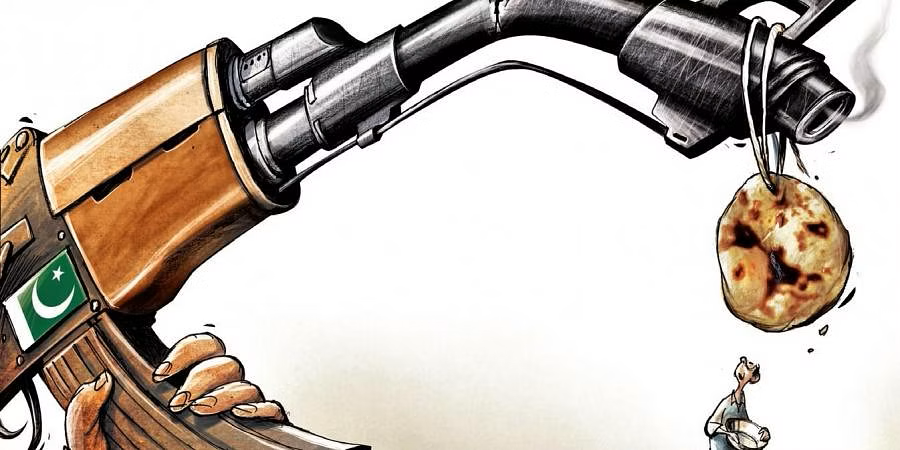

Pakistan has been off the rails for long and its current dynamics give no respite, be it internal politics, economy, sectarianism, radicalism, regional issues or foreign policy.

By Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (Retd)

Some of us in India have a Pakistan obsession; we love to keep our eyes on that nation and analyse its every development. Personally, I do not profess to do that but I do think Pakistan is one nation which gives enough opportunity to analysts to continually test their wares. It’s one of those nations where if you do not follow the happenings, you are outdated in two days. Things go wrong in India, too, just as they would in a nation of 1.4 billion: communal riots, agitations and ethnic instability. Yet, from a geopolitical angle, much of this gets subsumed under India’s economic success, political stability and rising stature in the world order.

There was a time when Pakistan, too, was feted and cultivated for a variety of reasons, none of which are valid today. Though not really a basket case, Pakistan has been off the rails for long and its current dynamics give no respite, be it internal politics, economy, sectarianism, radicalism, regional issues or foreign policy.

A temporary reprieve seems to have come its way in the last few weeks—in the economic domain. Most analysts always felt that with a degree of brinkmanship, Pakistan would not be allowed to go under. It did display remarkable ability to survive even in the face of an existential crisis. That was an achievement of sorts for former prime minister Shehbaz Sharif.

The Pakistan Army is determined to ensure elections, which could take place in November this year. The Army does not wish to rule, since most of the power is already in its hands; it is far more prudent to hold that power from behind rather than directly. That probably has the approval of the Pakistan Army’s biggest sponsor, the US. The latter is acutely aware of the dangers of letting things go adrift in Pakistan’s political scene. It contended with Imran Khan’s maverick attitude while he was the prime minister and even witnessed the rise of his street popularity.

The symbolism of Imran Khan’s presence in Moscow on the day the Ukraine War commenced is not something the US will forget in a hurry. Reports are indicating that Imran Khan’s constant reference to the foreign hand against him is a finger pointed at the US, which wanted him removed at any cost; the issue has yet to die down.

So, the election is likely to take place, as per the Constitution, with caretaker Prime Minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar, a known Army supporter, in the seat. His job will be to keep the nation on the rails in terms of both political and economic stabilisation for the next few months, with the $350-billion economy on survival mode after getting a last-minute $3-billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), averting a sovereign debt default.

In the next four to five years, Pakistan is due to service loans of almost $80bn. However, almost every step will have to cater to the directions of foreign funders and neutralizing all those internal forces who threaten to bring about an implosion of catastrophic proportions.

There is, of course, a contingency that could see Kakar’s interim stewardship extended. The outgoing government had approved the results of Pakistan’s latest census, which took place in May 2023. Pakistan’s Constitution needs elections to take place within 90 days after the Assembly is dissolved. It also lays down that polls must take place as per constituency delimitation, which must be marked according to the latest census.

The Election Commission of Pakistan needs at least four months to complete new delimitations. So, elections may not be held this year. Was all this contrived to give the constituents of the Pakistan Democratic Movement more time? This is something they have been demanding so as to allow the disastrous economic situation to stabilise, which anyway is highly unlikely.

All the above will perhaps lead to Pakistan’s politics being controlled for many years by the Army as proxy of the US, but with a ‘selected government’. With China reportedly seeing early signs of economic decline, a decrease in assistance could be on the cards. It does not necessarily mean a reduction of influence but a short-term standstill; the balance may thus once again tilt towards the US. The US-Pak relationship is perennial and this only recently saw reinforcement with the supply of ammunition to Ukraine from the Pakistan ammunition factories at Wah.

The Twitter handle ‘Ukraine Weapons Tracker’ said that Pakistan was part of an air bridge for supplying weapons to Ukraine. All this while, Pakistan has been sourcing wheat from Russia and a first consignment of Russian discounted oil has also been supplied to it, with the US turning a blind eye. A policy of higher tolerance seems to be followed by the US to allow Pakistan greater flexibility in foreign policy. In this context, Pakistan’s relationship with Saudi Arabia may not be as warm as it has historically been. Its refusal to join the Saudi-led military coalition in Yemen some years ago led to some cooling which is yet on recovery mode, and there is considerable recovery to be made.

ALSO READ | Article 370 abrogation: Four years on, a cautious elation

So, what can we expect in the run up to the elections if they are to be held in November or delayed by a few weeks? There are indicators of the return of former PM Nawaz Sharif, and there is a broad understanding within his Pakistan Muslim League (N) that he would be PM.

The question one asks is whether the Pakistan People’s Party with the Zardari-Bilawal element is seeking to be so easily subsumed. Bilawal is maturing, his articulation is excellent, and he is obviously ambitious. Is the PDM, therefore, likely to return, or will the elections be fought on individual manifestos—with a consensus after the polls if they do not achieve clear results? Much will depend on how the political scenario unfolds with reference to Imran Khan and his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). He is serving jail time for three years and is banned from elections for five. If the PTI without Imran can garner large-scale public support, it would be a different story, with the PDM coming back together, in a hurry.

What does this augur for us in India, with Pakistan at a low? If reports are true that General Asim Munir is working hard to make Pakistan’s governance more effective—and foreign policy is at a lower priority except in the economic domain—there should be a period of relative calm on the western borders and efforts towards J&K will remain low-key.

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (Retd)

Former Commander, Srinagar-based 15 Corps. Now Chancellor, Central University of Kashmir