Pakistan Prisoners of War 1971, Pawns in a larger Game

- December 22, 2021

- Posted by: admin

- Category: Pakistan

By – Col Ashwani Sharma (retd), Editor-in-Chief, South Asia Defence & Strategic Review

“It took Pak POWs of the 1971 war over two and a half years to be repatriated, they were but pawns in a bigger game”.

Someone else’s pain often escapes us, especially if it is an adversary. If the protagonist happens to be a unsung Prisoners of War (POW) of the enemy, the effect is pronounced manifolds. He is condemned to a life of ignominy, consigned to his fate as if losing a battle is equal to losing the battle of life, or even worse.

In the run-up to the 50th anniversary of the Indo-Pak war, 1971, there has been a huge amount of media hype, be it audiovisual, print, or Social Media. This is true in the case of India and Bangladesh; Pakistan for obvious reasons would prefer to forget that it ever happened. However, in the middle of the echo of such sentiments, I chanced upon an account by one Brig Mehboob Qadir (retd) of Pakistan who himself had been a POW having surrendered in Bangladesh. As a former officer of the Indian Army, and having celebrated Vijay Diwas every year, I was moved by his account. He does not complain about the treatment meted out to him by his captors. His lament is about the ignominy of surrender and to a larger extent, him being ignored by his own country and the indifferent treatment and apathy that the POWs received back home. Having read his account, and having pondered over it, I am convinced that POWs deserve sensitive care and handling by their own governments. But that’s not the focus of this feature. I plan to cover the larger issue of delayed repatriation of POWs, which was a major factor for their psychological breakdown and disorientation.

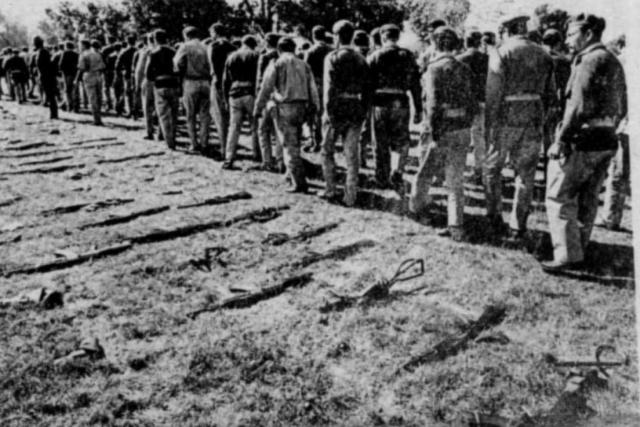

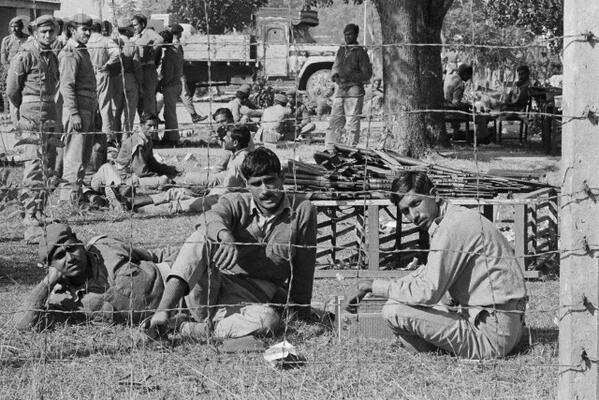

Repatriated in 1974, Pakistani POWs spent almost two and a half years in captivity. That’s an abnormally long time considering that the two countries are immediate neighbours and war clouds were over as soon as the ceasefire was declared and accepted by the belligerent nations. There was no fear of another conflict in the immediate future. Shimla Accord was signed between the countries on 02 July 1972, thus paving the way for the exchange of POWs. Yet it took almost another two years, till the Delhi declaration was signed in 1974 and the actual process started. For the record, India took approximately 93,000 prisoners of war that included Pakistani soldiers as well as some of their East Pakistani collaborators. 79,676 of these prisoners were uniformed personnel, of which 55,692 were Army, 16,354 Paramilitary, 5,296 Police, 1000 Navy, and 800 PAF. The remaining 13,324 prisoners were civilians – either family members of the military personnel or Razakars.

Protecting, housing, feeding, and looking after their daily needs, would have cost the Indian exchequer a fair deal of money and resources. What then was the hitch? Why did it take so long? A few pointers to solve the puzzle:

Let us go back to April 1972. DP Dhār, Mrs Gandhi’s close aide, and one of the core group members visited Pakistan on a quiet mission to discuss the POWs repatriation and the way forward between the two countries in the aftermath of war. He was whisked away to Murree Presidency under heavy security. Mr Aziz Ahmed, Bhutto’s special advisor was heading the Pakistani side. Ambassador (Sqn Ldr) Sami Khan, Sj, was then the protocol officer and remembers DP Dhar as a sharp, adroit diplomat. Having struck a good rapport with Sami with whom he happened to share Peshawar as their native place, one evening while taking a walk in the lawns of Murree Presidency, Dhar confided in Sami that Pakistani leadership did not seem to be in any hurry to get the POWs back. That there appeared to be some veiled motives and left it at that. The Indian delegation was of course surprised at this reluctance. Sami found it hard to believe as a large number of families in the West anxiously awaited their return. Sure enough, Sami brought the matter up with Mr Aziz Ahmed. Aziz then told Sami that the stance was to keep the Indians from using POWs as a bargaining chip for settling Kashmir. Clearly, Bhutto and his team had pre-empted the Indian strategy to use POWs as leverage to their advantage.

The second plausible reason for the delay was Bhutto’s intense desire to put the military down, make them look like the fall guys, and take the blame for all their failures. It can be traced back to his shenanigans at the UN General Assembly where his actions betrayed the cause, even though his filibustering earned him a few brownie points. Knowing the sharp intellect Bhutto possessed, it is reasonable to infer that his actions were in fact part of a well-thought-out strategy to make the Army’s position untenable in East Pakistan. After the surrender, Bhutto showed no urgency in getting the POWs back home. He wanted them to be humiliated further while he established firm control back home. Bhutto’s treatment of Yahya and subsequent sacking of General Gul Hassan and the Air Chief Rahim Khan fits in well with this plot. Ironically, India was left to protect and look after the POWs. Post Yahya period when certain human rights activists asked Mrs Gandhi why was India holding on to 90,000 plus POWs, she replied,” It’s not what meets the eye. Why don’t you put this question to the leaders of Pakistan?” She was pointing towards convenience or connivance on part of the Pakistan government.

The last but perhaps the most significant reason for delaying repatriation was the possibility of a large-scale outrage within a resentful Pakistan Army and the irate West Pakistan population, extremely disenchanted with the establishment over its failure on all counts resulting in a humiliating defeat. The POWs consisted of a large number of officers who were convinced that they were pushed into a hopeless situation by a blundering political and military top brass. The rank and file supported this view and were eager to seek answers.

This did not bode well for the new political and military leadership of Pakistan, who were deliberate in their plan to delay the arrival of POWs till the situation is firmly under control. The fact that it also robbed India of the strategic advantage suited them very well. So cleverly the blame was apportioned fully at Yahya in a bid to deflect responsibility for the debacle.

Justice Hamood-ur-Rehman Commission set up by the Bhutto government was specifically mandated with “To enquire into and find out the circumstances in which the Commander Eastern Command surrendered and the members of the Armed Forces of Pakistan laid down their arms and a cease-fire was ordered along the borders of West Pakistan and India and along the cease-fire line in the state of J&K”. What would such a commission do with such terms of reference except for finding faults with the Army?! Why was the commission not charged with the responsibility of finding out the reasons for the secession of East Pakistan?