Lockdown: How we pay for Centre-States trust deficit

- March 7, 2020

- Posted by: Mr Manoj Mohanka

- Categories: Domestic Issues, General Topics

‘A hundred days later, it is a moot point whether the lockdown has been partially or totally effective, or, as sceptics indicate, plain ineffective.’

‘Did it actually deflect infections and the loss of lives, or was it merely a hasty decision rammed down the populace’s throats that choked the economy and caused the searing tragedy of dispossessed migrant workers?’ ask Radha Roy Biswas and Manoj Mohanka.

All illustrations: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

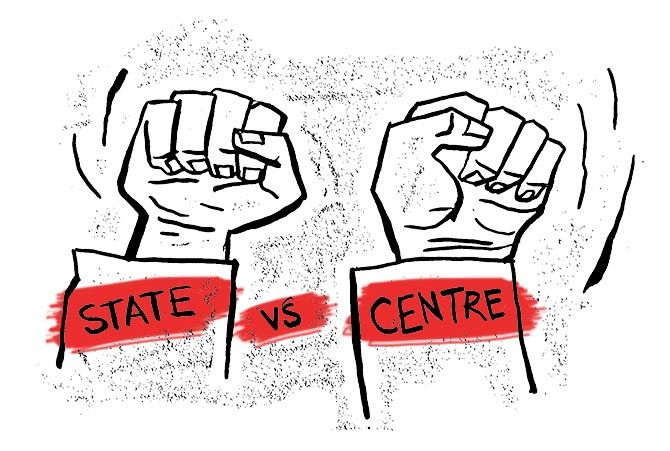

At any given time in the life of a nation, trust and cooperation between the states and the Centre are the key to the state of the Union.

So also, for a lock-down or unlocking.

On March 24, a nation of 1.3 billion people was brought to a standstill when Prime Minister Narendra Modi imposed a nationwide lockdown starting midnight to stave off the COVID-19 pandemic.

A hundred days later, it is a moot point whether the lockdown has been partially or totally effective, or, as sceptics indicate, plain ineffective.

Did it actually deflect infections and the loss of lives, or was it merely a hasty decision rammed down the populace’s throats that choked the economy and caused the searing tragedy of dispossessed migrant workers?

While this is, and will continue to be, debated endlessly, the primary issue now, is the way the nation is unlocking: with states taking charge of their own staggered path to reopening, after the PM removed the blockade, and ‘directed’ the states to do so in a way that they deemed appropriate.

The state-wise unlocking will have equal ramification for lives and the economy.

Both the Centre-directed lockdown and state-driven reopening display the balance of power and the dynamic between the states and the central government.

And it may be worth a look to see what the challenges are, and what needs be in place for either to work.

As any school child knows, our Constitution is an amalgamation of many inspired undertakings — the American, French and Irish constitutions, foremost.

The august team of drafters avowedly wanted to learn and took from the best around the world to lead our young nation.

In the process they drew on the rights, responsibilities and directives of governance enshrined in those hallowed documents, to create an entity with a strong executive centre, along with a federalist structure that devolves certain rights and responsibilities to the states, with checks and balances for both.

But also, as we have discovered anew, a possibility of huge inbuilt tension based on power play.

On the Republic’s federalist spirit, the chairman of the drafting committee, Dr B R Ambedkar, had this to say:

‘Though the country and the people may be divided into different states for convenience of administration, the country is one integral whole, its people a single people living under a single imperium derived from a single source.’

When the PM announced the lockdown on March 24, he was within his Constitutional rights to do so.

But states were not consulted, and the dissonance showed.

States complied with the lockdown with their own interpretation — varying from a defiance of the central writ, to a limited, reluctant compliance, to going along entirely.

Their own political agendas and vote bank considerations, oft at conflict, became a spoiler in the process.

The gap was more visible where the states were ruled by non-NDA affiliates, which is not to say that they didn’t do well.

Some, like Kerala, became shining examples of how the states ought have tackled the crisis: steering their own ship while taking full advantage of the Centre’s help as appropriate.

How much exactly the efficacy of the lockdown was impacted by states’ variance in instituting it, is hard to tell.

However, one does not have to be a close observer of Indian politics to know that ‘politics’ certainly led to different trajectories for the virus spreading across the country.

The lockdown was criticised by many state chiefs, as one more instance of the Modi government’s tendency to spring surprises and ram hasty decisions down the country’s throat, or as others alleged, delayed to accommodate the ruling party’s election aspirations by way of instituting a coup in MP.

Truth or canard, it certainly exacerbated the long-standing discord between states and the Centre.

As the COVID-19 count continues to surge, we can ask, did the fractious cacophony that is the Indian polity, get us — the citizens — shorted both by the Centre and the states?

Nowhere is this more clearly visible than West Bengal where the chief minister has asked for the cessation of international flights (Vande Bharat evacuation ones run by Air India, which were very few in any case) as she wanted the Centre to handle the mandatory institutional quarantine of the arriving passengers with the Centre wishing the State govt take care of it.

Even as that impasse continues, the Bengal government has asked for domestic flights to Kolkata from Delhi-Mumbai-Pune-Nagpur-Chennai-Indore-Ahmedabad-Surat stopped from July 6 until July 21.

Why did the Centre do this in the way it did? Could it have been done better or differently? Well, it certainly had its basis in law.

The Centre took recourse to Article 256 of the Constitution which stipulates that the Centre can give directions on how to implement laws made by Parliament.

Article 257 indicates that the executive power of the states should be exercised in a manner that does not ‘impede or prejudice’ the executive power of the Centre.

The Centre also took recourse by invoking two other laws which provided the statutory basis for acting against the pandemic: The 1897 Epidemic Diseases Act and the 2005 Disaster Management Act].

A more effective national lockdown could perhaps have best been implemented under a national emergency being declared, under Article 352.

In this provision, the state government administrations become subordinate to the central government, as all executive functions of the state come under the control of the Union government in the event of war/external aggression and ‘armed rebellion’ as happened in 1962 and 1971 during the two wars India fought.

The Emergency declared by then prime minister Indira Gandhi 45 years ago was under the same Article but it allowed ‘Internal disturbance’ to be adequate reason for a declaration.

This clause was repealed by the 44th& Amendment act in 1978 and hence not possible to invoke.

Moreover, this crisis, not being war in the traditional sense, left no room for such an Article 352 emergency to be declared.

Perhaps it was this lacuna or lack of Constitutional authority that made all the difference in a lockdown — where the Centre directed the states in an order but could not hold them to its implementation.

Multiple discussions are said to have taken place out of the public eye between the Union home secretary and the chief secretaries of various states, but the command and control structure needed to tackle a crisis, augmented with political and administrative will, seemed missing.

Officials appeared to be working at cross purposes.

The voluntary cooperation of state leadership, so vital in executing a national order across the country, was absent in many instances, except for the initial period of shock.

State bureaucracies were caught between directives and objectives of the Centre and conflicting directions of their own state’s chief ministers.

As a result, we had a lockdown announced with the best of intentions, but not the success that it deserved or could have achieved.

Instead, we got a migrant labour crisis and a COVID-19 ticker that now reads 604,461 cases, 17,834 deaths (as on the morning of July 3) and counting.

By May, the migrant crisis had exploded into the national consciousness and on mobile screens even as the economy continued to haemorrhage.

States began to feel the pressure and heat from their businesses and other constituencies, and clamoured to remove the lockdown.

This time, the Centre decided to invoke the other aspect of our Constitution — what may be called the federalist impulse.

The process involved well publicised Centre-state dialogues, and the states were directed to craft their own re-openings within certain broad guidelines.

Whether it was because the Centre’s purpose had been achieved or it finally recognised that the problem could not be managed from their vantage point alone in the face of ground realities and opposition from too many quarters, will remain anyone’s guess.

The migrant crisis certainly played a part.

That workers, with their daily wages gone, would need to return to safety of their homes, was lost in the panic and din of the first couple of weeks, and the haste in implementing the lockdown.

It could be argued that the central government didn’t have a choice and had to act fast, given the utter chaos that was unfolding around the world and the fears of an out of control contagion.

It had little time to plan, and therefore had to shoot before it could aim.

But it is undeniable that these workers became the biggest victims of the pandemic.

Would it have been better if the states had been taken on board?

Could some uniformity may have been expected, with less of a variance in states’ implementation, had a conversation taken place at the outset pre-announcement on 24th March 2020?Had the states been consulted, they may have pleaded for trains to run for the ‘return of the natives’ working across the length and breadth of India.

It is also possible that some states might have picked up cudgels to keep migrants from moving, and contained the spread to bigger cities — stopping the virus’s migration to smaller towns and villages.

Some states may not have assented at all, or merely dragged their feet to thwart the Centre’s plans.

While second guessing state actions serves no purpose, now that the pandemic is wild and loose in the country, it is clear that the nation is paying for the trust deficit between the Centre and states, as much in the unlocking, as in the lockdown.

This is a breach that needs to be filled, and filled quickly, not just for a war on an invisible enemy, but also for the other wars with the enemies at our gates.

As W B Yeats wrote in the second coming, ‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world…’ For the Centre to hold and anarchy not be let loose, the Centre and states must hear each other.