India-China dynamics in turbulent times : Civilisational ties and border dispute (Part I of three-part series)

- June 16, 2020

- Posted by: Lt Gen PR Kumar (Retd)

- Categories: ASEAN & ARF, China, Foreign Affairs, Military, Strategic Affairs

What does a big, unpopular, ‘different’ boy with very few friends do if he is suddenly picked on by most of the class? Admittedly he did something horrific bringing unimaginable misery to himself and the entire class, but ironically the other big boys had also done innumerable equally nasty things without being castigated. He either comes out arms flailing at anyone or everyone, especially those in close proximity to him or retreats into a shell. Sounds simplistic but astoundingly it rings true because the destiny of nations has most often been shaped by rulers with power and authority – Nazi German dictator Adolf Hitler, former Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, former US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, former British prime minister Winston Churchill, US President Donald Trump, Russian President Vladimir V. Putin, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

There are three groups – anti-China led by the US, pro-China a very small but still powerful group, and third the fence-sitters (run with the hares and hunt with the hound’s variety) who surprisingly are the largest group, mainly because of geography and economic connect. Realpolitik is being played out with Machiavellian ferocity, by all. No one can play above board or altruistically; national interests and future strategic space is the key for survival/growth/ domination. Majority action, however, by no means guarantees either moral or legal sanction.

When you’ve got a house full of sick people you don’t usually go out looking for a fight. But China (Chinese Communist Party to be more precise), led by Xi Jinping, is doing exactly that. Like a high-stakes gambler, he has rolled the dice – while COVID-19 epidemic rages – to see what he can win on the security and geopolitical front. Muscle flexing has been impressive; intimidating or sinking fishing vessels (Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, even Japan); threatening Southeast Asian naval ships by locking missiles; conducting exercises to intimidate and develop specific skills needed to invade Taiwan; use belligerent language at all adversaries including stating the intent of “reunification of Taiwan” openly; activities in exclusive economic zones of neighbours, Japan included. Closer home, with obviously serious implications for India, engage in physical jostling, intrusions (presence of more permanent nature in Indian territory), force build-up, digging in and building infrastructure in four/five locations, in North Sikkim and East Ladakh, thus changing the status quo of an already tense unresolved land boundary; and finally ‘wolf diplomacy’ a recent phenomenon knowing its adverse impact.

The situation is made worse by an equally belligerent US and allies (and many other nations joining the crowd, but who dare not speak alone), who outwardly want reparation for COVID, but in strategic terms pull down the dragon before it breathes fire on them.

Within this turbulence this three-part article will dwell on India-China relations – India-China civilization connects and genesis of the boundary dispute; the way forward for resolution of boundary impasse; and probable two-and-a-half front continental conflict strategy and scenario.

India-China civilisational connect

Two of the oldest civilisations and largest nations of Asia, India, and China, are also immediate neighbours, who enjoyed trade, cultural and spiritual two-way relations from time immemorial. The exchange was facilitated by four routes of communications: the Central Asian Route or Silk Route; Assam-Burma and Yunnan Route or Southern Silk Route; Tibet Nepal Route; and the Sea Route or the Maritime Silk Route. The first credible information about the India-China interactions is provided by Si Maqian (BC 145 – BC 90?). The great Chinese historian in his masterpiece Records of a Historian: Foreigners in SouthWest. He narrates that while visiting Central Asia, he saw Chinese and Indian products, confirming the fact that formal relations existed during the 2nd Century BC. Subsequently, at regular intervals, historical writings by Ban Gu (32-92AD) and others, spoke of improved and increasing relations (including diplomatic) especially during Tang (618-907), Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties.

Maritime activities were intense and it is reported in various sources that in Canton (Guangzhou) there were ships of Indian, Persian, and Sri Lankan merchants. Calicut and Cochin in India rose to prominence as the new ports. References of other seaports such as Mahabalipuram, Goa, Nagapattinam, Quilon, Nicobar, Mumbai, Malabar, Calcutta, and many more could be found in various Chinese literary sources. Indian astronomy, calendar, medicine, music and dance, sugar manufacturing technology, etc. made their way to China.

The spiritual linkage transformed this relationship completely and took it to a new high. When exactly Buddhism disseminated into China is a debatable proposition. However, the most prevalent version is the famous dream of “golden Buddha” by Han emperor Ming Di (58AD-75AD) when two highly proficient Buddhist scholar monks, Kashyapa Matanga and Dharmaraksha, visited China, and subsequently, wave after wave followed. Of special mention are Kumarajiva (343-413) who was accorded the honour of RajyaGuru by Emperor Yao Xing, and Xuanzang (7th Century). Incredibly, Bodhidharma went to China in 6thh century AD and is believed to be the founder of Shaolin martial art in China. School books talk of Faxian’s travels (monumental work Accounts of a Buddhist Country) to India and Xuanzang (The Journey to West during Great Tang) and Yi Jing who studied at Nalanda and became proficient in Sanskrit. frescoes of Kizil and Dunhuang houses the portraits of many Hindu deities like Hanuman, Ganesha, Vinayaka, Laxmi, and Shakti.

Statues of Lord Krishna and Shiva have been unearthed from Quanzhou and Dali in China pointing to large settlements of Indians in China. Owing to these cultural and material linkages, both India and China benefited immensely in the field of literature as also science and technology. Indian stories, fables, art, drama, and medicine reached China. Along with Buddhist linkage, Hinduism also made inroads to China. This could be established from the discoveries of Hindu cultural relics at sites such as Lop Nor in Xinjiang, Kizil, and Dunhuang grottoes in Gansu, Dali in Yunnan, and Quanzhou in Guangdong provinces of China. There is no historical precedent of any confrontation between China and India for thousands of years up to their achieving independence, which is astounding and speaks volumes of the culture and spiritualism in both civilisations.

The gradual eastward expansion of western colonialism resulted in India being completely colonized by the British and China gradually transformed into a semi-feudal and semi-colonial society. The anti-imperialist efflorescence of the Indian and Chinese people manifested in a major way as a challenge to the colonial order for the first time during the First War of Indian Independence (1857-59) in India and the Taiping Uprising (1850-1864) in China, which was the first time Indian soldiers stationed in China switched over to the Taipings and fought shoulder to shoulder against the imperialists and the Qing government. This rapprochement continued when the organised struggle for national independence was launched by the Indian and Chinese people. Nationalists like Surendermohan Bose, Rashbehari Bose, M.N. Roy, Barakatullah, Lala Lajpat Rai, and many other outstanding pioneers of the Indian freedom movement maintained good contacts and friendship with Sun Yat-Sen, the father of modern China. Through Sun Yat-Sen, the Japanese connection was cemented. The Indian National Army and the Ghadar Party prospered with material and moral support from Chinese and Japanese leaders. Chinese people identified with Mahatma Gandhi and freedom struggle and all events like the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920-22), Civil Disobedience Movement (1931-34) were covered and followed widely by Chinese media and people.

However, most Chinese leaders never approved of the doctrine of non-violence. India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited China in 1939 and after independence proclaimed the infamous words ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’ (Indians and Chinese are brothers). He naively dreamt of a world order dominated by India and China. President Chiang Kai-Shek visited India in 1940, especially to break the ongoing deadlock between the British and the Congress and also met Mahatma Gandhi. India was the first non-communist nation to recognize China and established diplomatic relations on April 1, 1950. India initiated and strongly supported China’s membership in the United Nations Security Council, voted against China being labeled the aggressor in the Korean War and there was reciprocation from the Chinese side.

The famous Panchsheel (five principles of co-existence) was initiated by both. The geopolitical and strategic equations of both India and China with the two superpowers the US and erstwhile USSR, which waxed and waned, was largely instrumental in shaping post-independence relations. While India never had hegemonistic tendencies, China the ‘middle power’ always wanted to restore its past glory by any means, which included grabbing/occupying land and maritime zones based on its perception of past ownership. Independence exacerbated the grievances of China against India; unresolved border, viewing India as a stooge of the West, and perception of Indian interference in Tibet.

India’s perception of the India-China border issue

Colloquially, the terms boundary and border are used interchangeably, a boundary is a line between two states that marks the limits of sovereign jurisdiction. In other words, a boundary is a line agreed upon by both states and normally delineated on maps and demarcated on the ground by both states. A border, on the other hand, is a zone between two states, nations, or civilizations. It is frequently also an area where people, nations, and cultures intermingle and are in contact with one another. Three distinct steps are involved in boundary-making. The first step is to have an overall political understanding of the basic boundary alignment. This step is referred to as allocation. The second is to translate this general understanding to lines on a map and this process is called delineation. The third and final step is to transpose the lines drawn on a map to physical markers on the ground. This step is called the demarcation. Quite clearly therefore a boundary settlement is not a simple drawing of lines on a map or a demarcation on the ground. It is a significant political act.

The principle of ‘uti possidetis juris’ enshrined in international jurisprudence was invariably followed when it came to settling boundary claims. This principle states that whenever a state becomes independent, it automatically inherits colonial boundaries and that any effort to occupy or violate state territory after it became independent would be considered ineffective and of no legal consequence. This principle was recognised by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as legally valid in the Burkina Faso v Mali (1986) case. Further, if a state acquires knowledge of an act which it considers internationally illegal, and in violation, and nevertheless does not protest, this attitude implies a renunciation of such rights, provided that a protest would have been necessary to preserve a claim. This appears the only logical reason that former Chinese premier Zhou en Lai rejected Nehru’s offer outright to take the dispute to the ICJ conveyed in his letter of January 1, 1963.

Specifics of the disputed border

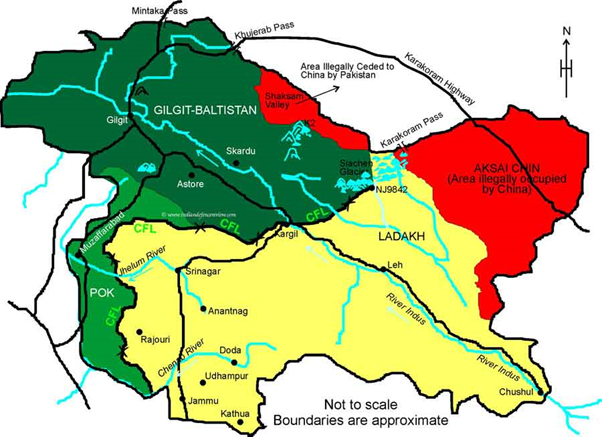

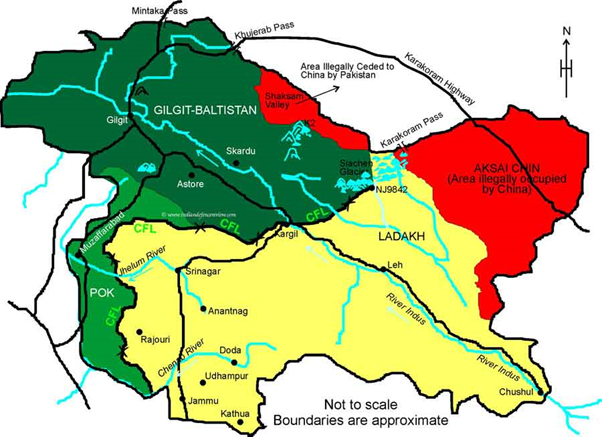

The disputed areas between China and India can be divided into three sectors: Eastern, Western, and the Middle. The Indian stance is that the Sino-Indian boundary is 3488 Km (includes 523 km Pakistan Occupied Kashmir-China Section) in length, with Western Sector being 1597 km, Middle Sector 545 km and the Eastern Sector 1346 km in length, apart from 5180 sq km illegally ceded by Pakistan to China, namely the Shaksgam Valley in the Western Sector.

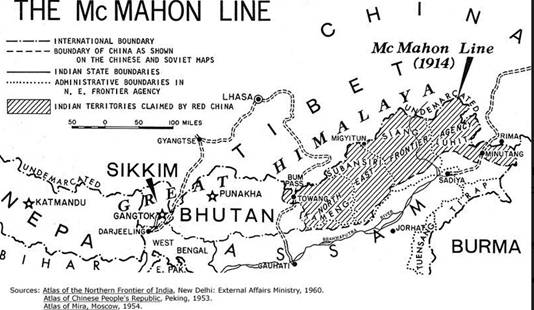

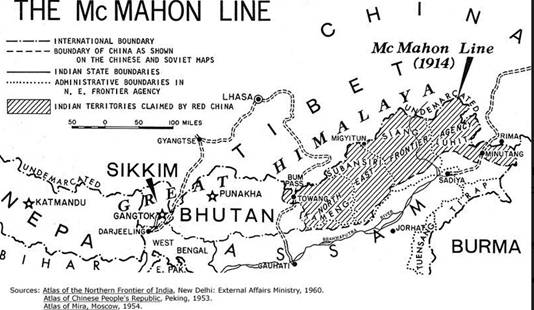

Eastern Sector (refer to maps 1 & 1A)

As regards the Eastern Sector, Tibet, and India signed the Simla Convention that gave birth to the McMahon Line separating Tibet from India on July 3, 1914, more than a hundred years ago. India accepts the McMahon Line as the international boundary between China and India with minor modifications in interpretation, in accordance with the internationally accepted Watershed Principle which was the intent of the chief British negotiator, Sir Henry McMahon. Although the Simla Convention recognised that ‘Tibet forms part of the Chinese territory’ (for purely political purposes by the British during the Great Game with Russia, but later on walked away from above stance), the then Chinese authorities did not sign the Convention as they objected specifically only to Article 9 of the said Convention that laid down the boundaries between Inner and Outer Tibet (viz proposed boundary between China and Tibet, which ipso facto implies acceptance of the boundary between Tibet and India).

Other than that, the Chinese authorities made it amply clear, on several occasions that they did not object to any other Article, including that which showed the McMahon Line. From the time of the signing of the Simla Convention on July 3, 1914, till January 23, 1959, when PM Zhou wrote a letter to Nehru, the Chinese never raised any formal objections to the McMahon Line; although they had many opportunities to do so. The Chinese representative, Ivan Chen, not only fully participated as a delegate, but on an equal footing with the Tibetan representative. One extremely pertinent and important observation is that China settled its outstanding boundary issues with Burma in 1960, along with the Burmese sector of the McMahon Line (importantly, in 1914 when the Simla Agreement was signed, Burma was an integral part of India), the settlement in physical terms is virtually an adoption of the same alignment, with some minor give and take. On resolution, the modified new line was ratified as “The Burma-China Boundary Treaty of October 1, 1960”. China is very sensitive about the historical imperial/colonial baggage especially involving boundaries and doing away with the moniker McMahon Line.

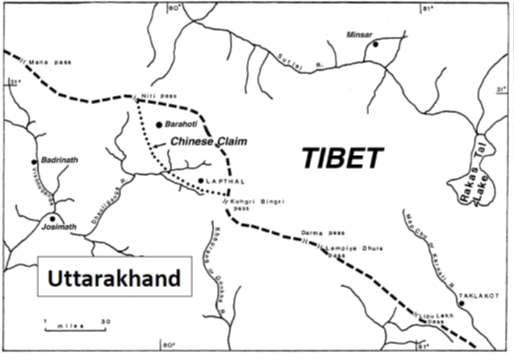

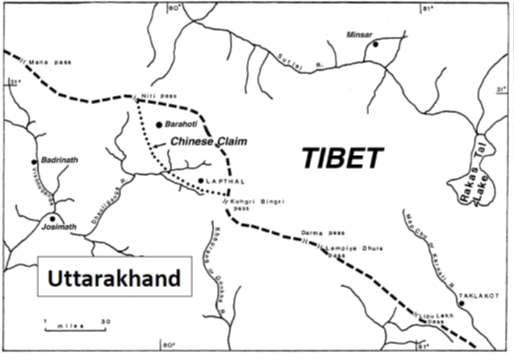

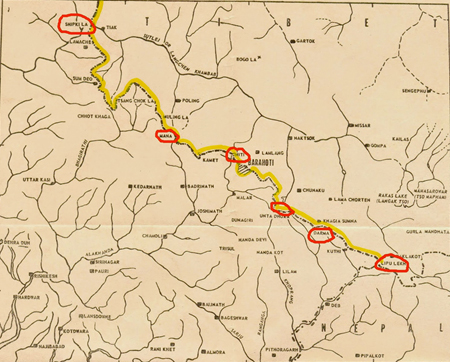

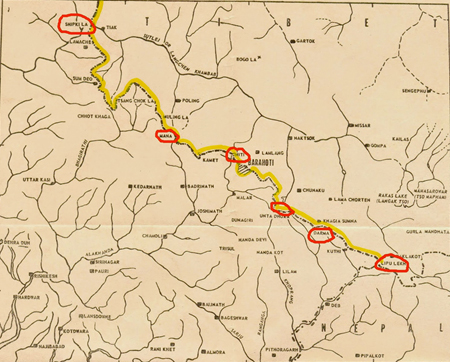

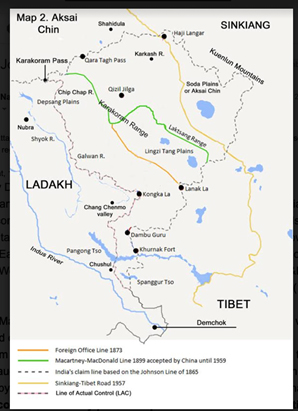

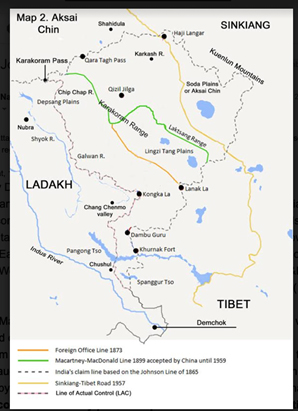

Middle Sector (refer to maps 2 & 2 A)

The boundary runs along the crest of the Himalayas in the Indian states of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh. It is the least disputed sector and differences exist in mainly four areas viz Spiti, West of Shipki pass, Nilang-Jadang, and Barahoti. All these being south of the crest line, the Chinese claims are tenuous at best, keeping the internationally accepted Watershed Principle in mind. The disputed areas are under Indian control.

Western/Ladakh Sector (refer to map 3)

In the Middle and Ladakh/Western Sector the boundary was based on various lines agreed to by the Tibetan government with the rulers of Jammu and Kashmir state and Himachal Pradesh from the 17th century onwards. There are three historical lines depicting the India-Tibet boundary: the Johnson (1865), Johnson-Ardagh (1897) and the Macartney-MacDonald (1899) lines, apart from the Treaty in 1842 between India, Tibet, and China which was signed by all three authorities. All lines are well documented and the historical narrative forming the basis of these lines and their relative acceptance/non-acceptance by the principal actors (British, China, and Tibet) is not being recounted.

Upon independence in 1947, and the accession of J&K to the Dominion of India by the then ruler Maharaja Hari Singh, the government of India accepted the Johnson Line as the basis for its official boundary in the West, encompassing Aksai Chin. However, India did not claim the Northern areas near Shahidulla and Khotan, for inclusion within Indian territory (map 3). It is pertinent to point out that the Chinese have never provided a specific alignment along with the Western Sector (specifically after their independence in 1949) and have changed their stance innumerable times.

Shaksgam Valley

The Shaksgam Valley (5180 sq km) or the Trans Karakoram Tract is part of the Hunza-Gilgit region of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) and is an integral part of J&K claimed by India, was controlled by Pakistan and ceded illegally to China in March 1963.

(The writer is an Indian Army veteran. He was Director-General of Military Operations. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at perumo9@gmail.com)

Map 1

Figure 1:Indo-China Border

Figure 2: McMahon Line

Map 2A

Map 3

Figure 3- India China Border East Ladakh

References —

India-China Relations: A Historical and Civilizational Perspective by Cr BR Deepak; dated 15 Dec 2010; China Centre for China Studies, Link https://www.c3sindia.org/archives/india-china-relations-a-historical-and-civilizational-perspective/.

India-China Boundary Issues: Quest for Settlement, by Ambassador R S Kalha, Pentagon Press, 2014

Oppenheim. International Law: A Treatise (London: Longman, Green & Co 1955), pp. 874-5.

L/P&S/10/344.[File No.P.464/1913, Pt. 5] Proceedings of the 7th Meeting/Annexure 3. Chen to McMahon, 26 April 1914, and L/P&S/10/718.[File No. P.3260/1917 Pt.6] John Jordan to British Foreign Office No. 250 dated 30 June 1914 contains memo from Wai Chiao Pu [Chinese Foreign Office] dated 29 June 1914

Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People’s Republic of China on the Boundary Question (Government of India, Ministry of External Affairs, February 1961), published by the Government of India after talks with the Chinese in 1960- -61 and stated in the book Choices by Shivshankar Menon

Maps on India-China boundary- Map 1 from google images, rest Digital Archive International History Declassified; digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org, and books by Claude Arpi