Golden jubilee of 1971 war: Triggering a new resolve

- February 24, 2021

- Posted by: Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (Retd)

- Category: Strategic Affairs

India is stepping into the 50th year after its spectacular military campaign that led to Pakistan’s capitulation on 16 December 1971. Current public knowledge of those landmark days remains severely limited. The Golden Jubilee year of the successful completion of the 14-day war will no doubt be celebrated but it must equally be utilised to enhance public knowledge on how victory was achieved. People are aware of the 1971 Indo-Pak war as a dot in history but not with the nuances of it.

Pakistan existed from 1947 to 1971 with two segments separated by 2,000 km of India. United only by religion, East and West Pakistan had major cultural, linguistic and ethnic differences that could not allow their integration as a nation state; the entire two-nation theory based on which Jinnah’s Pakistan was created struggled to justify its existence. Proportionally in minority, West Pakistan attempted to dominate the East in every way, the Punjabis, Sindhis, Balochs and Pakhtuns of the West looking down upon the Bengalis of the East and hoisting their perceptions on the majority.

Language was one of the major issues as was the allocation of funds. Attempts to make Urdu the dominant language of the state was the trigger which led to a chain of events that ultimately saw efforts to scuttle the majority electoral mandate won democratically by Sheikh Mujibur Rehman’s Awami League in December 1970. Wishing to avoid rule by the Bengalis, the Army in connivance with the crafty Zulfikar Bhutto avoided the convening of the Assembly session that would have led to Sheikh Mujib proving his majority and thereby being handed the reins of power. Instead, the Army went on a killing spree, many times referred to as a virtual genocide. Sheikh Mujib, although arrested, declared secession from Pakistan and a war of independence began.

For India, the choice was to either watch from the sidelines the slaughter of innocents and the pouring in of thousands of refugees into its territories or proactively do something about it. The global community had no resolve to end the internal turbulence in Pakistan but India was suffering the consequences of it. PM Indira Gandhi called the then Army Chief General Sam Manekshaw to a meeting with her important Cabinet colleagues and asked for his readiness to undertake proactive operations to enter East Pakistan, put an end to the massacres by defeating the Pakistan Army and help create an independent state for the Bengali people of Pakistan.

Manekshaw’s conversation with Indira Gandhi’s cabinet is legendary and mentioned by him in his numerous speeches, although many today contest that no official record of the same exists. What is clear is that Manekshaw told the PM that entering the erstwhile East Pakistan territory would be tantamount to a declaration of war with Pakistan on both eastern and western fronts, which he was in no position to fight given the state of the Army and the timing of the events. He demanded time and resources to ensure the Army was fully ready to deliver what the government demanded.

Among the constraints he listed were lack of spares and ammunition. Regarding the timing, he did not wish to engage Pakistan in the approaching summer when China’s PLA could prevent our pulling out troops from the northern borders. In addition, the war in Punjab and north Rajasthan would lead to movement of our tanks destroying the summer crop, which would be most harmful for an economy already stretched by the war effort. Lastly he informed the PM that the war could extend to the monsoon season when the east-west movement of reserves would be severely hampered by the state of communications in northern India. The PM could not have had more sage advice given by a professional soldier, frank and to the face.

The PM gave Manekshaw a free hand in planning while she undertook the diplomatic campaign. The signing of the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship was a landmark achievement to bolster the confidence in the military effort underway. Pakistan perceived that India could not fight on two fronts and that the fear of Chinese intervention would dissuade it from launching a war. When it discerned serious Indian intent, Pakistan decided to trigger hostilities on the western front in the fond hope that it could prevent India undertaking operations in the East; 3 December 1971 witnessed air attacks on Indian airfields all along the western front, which gave New Delhi sufficient reason to unleash its plan.

Manekshaw decided to fight limited on the western front and go for a focused campaign to liberate East Pakistan. Only once marked success was achieved in the east with no loss of territory in the west would he allow his commanders to undertake any offensive operations in the latter. In the east, he built a sizeable advantage by concentrating three corps size formations and tasked them to advance rapidly, bypassing major opposition. The Indian Army engineers played a significant role in bridging the many rivers and creating loop roads for sidestepping main arteries.

Capture of Dacca was not the initial aim. It was due to the operations led by Lt Gen Sagat Singh, in command of 4 Corps, which were unconventional and achieved such spectacular success in quick time that capture of Dacca became a possibility. With Dacca as the revised centre of gravity, rapid concentration was achieved around it even as islands of Pakistani resistance had enough ammunition and supplies to last a month.

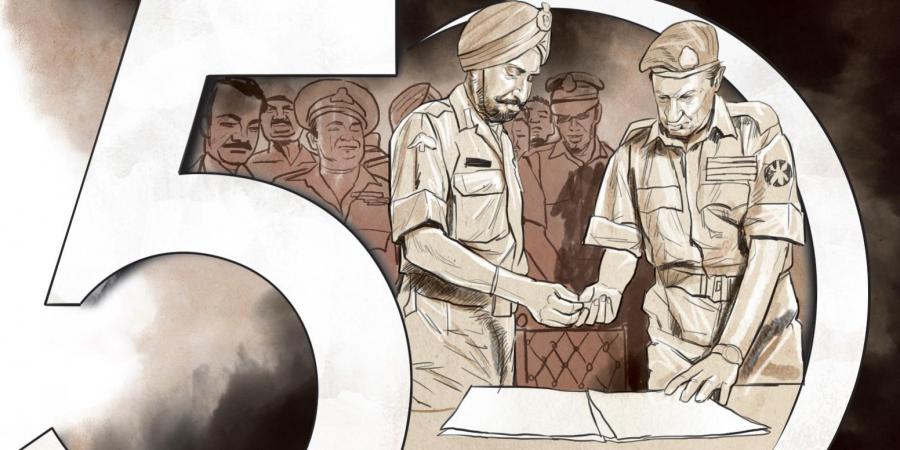

With all means of reinforcement cut off, the Indian Air Force ruling the skies in the east and progressively in the west, and the Indian Navy undertaking spectacular operations against the Karachi harbour threatening Pakistan’s national logistics, the die was cast for a massive Pakistani defeat. It eventually happened with the surrender on 16 December 1971 at Dacca’s famous Maidan as Lt Gen A A K Niazi handed over his pistol to Lt Gen Jagjit Aurora, India’s Eastern Army Commander and 93,000 Pakistani servicemen overnight became prisoners of war.

Bull-headedness and inability to foresee anything beyond conflict initiation became a characteristic of Pakistan’s leadership. Hopefully 2021 will see a mature awakening there for the need to pull back from conflict as the only means of resolving differences.

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (Retd)

Former Commander, Srinagar-based 15 Corps. Now Chancellor, Central University of Kashmir

(atahasnain@gmail.com)