Deep State is the convenient bogeyman of modern politics. It’s entered India too

- April 1, 2025

- Posted by: admin

- Category: India

Sometimes, those who claim to be part of the deep state ascribe to themselves a larger-than-life role in state affairs—for example, AS Dulat and Asad Durrani in their 2018 book.

Circa 1900: Rudyard Kipling wrote Kim, placing the eponymous hero at the centre of the Great Game of espionage between the British Empire and Russia in the 19th century. The book is set after the Second Anglo-Afghan War, which ended in 1881, but before the Third, likely in the period 1893–98. Kim, short for Kimball O’Hara, is an impoverished Irish orphan who lives on the streets of Lahore and works for Mahbub Ali, a Pashtun horse trader. He later befriends an aged Tibetan lama, accompanies him on his journey along the Grand Trunk Road, learns about the Great Game, and is eventually recruited by Mahbub Ali, who works for the British Secret Service in their quest to extend influence in both Afghanistan and Tibet.

Whether or not the Great Game—the expression used by British imperialists to describe the perceived expansion of Russian influence in Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Tibet—actually existed, the fact remains that surveys were undertaken, expeditions mounted, spymasters recruited, and novels written, even as soldiers lost their lives. Taking a cue from Viceroy George Curzon, all pro-establishment papers—from the Civil and Military Gazette of Lahore to The Pioneer of Lucknow, The Statesman of Calcutta (now Kolkata), and The Times of India of Bombay (now Mumbai)—concurred that Tsarist Russia posed a real threat to the jewel in Britain’s crown. A hundred and twenty years later, historians remain sceptical of Curzon’s assertions.

Loaded: 1.70%Fullscreen

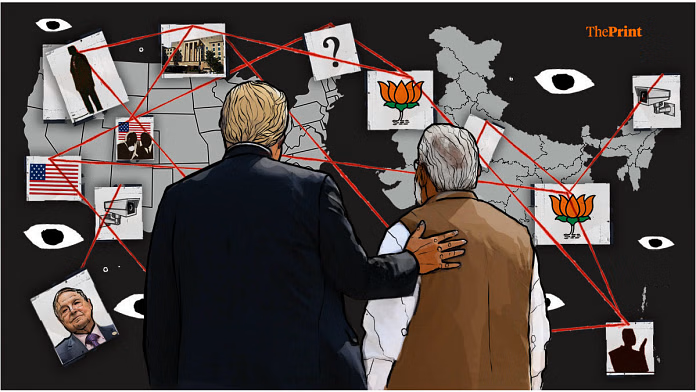

Is the hue and cry about the Deep State similar to the Great Game? Whether or not it exists, whether it operates in all countries, and whether the ‘deep state’ of one country is connected with others through the dark web or entrenched corporate interests remains unclear, as the discourse is more ideological than empirical. Sometimes, those who claim to be part of the deep state ascribe to themselves a larger-than-life role in state affairs—for example, AS Dulat and Asad Durrani in their 2018 book The Spy Chronicles: RAW, ISI and the Illusion of Peace. Their claim to be arbiters of one of the most tense and difficult relationships in the region has been widely critiqued by reviewers.

Also read: Riddle me this: India-US ties ‘span seas to stars’ and BJP goes after deep state and Foggy Bottom

What is the Deep State?

The term first gained wide currency in the context of Türkiye as derin devlet, which literally translates to “deep state” in English. In Türkiye, it refers to a non-elected military elite dominating elected governments, especially when they attempt to dismantle the secular foundations of the Republic, established by Mustafa Kemal Pasha after the abolition of the caliphate in 1923. In Pakistan, “deep state” refers to a government controlled by powerful military leaders, as documented by Stephen Cohen in The Idea of Pakistan and Ishtiaq Ahmed in Pakistan: The Garrison State. Elected governments in Pakistan have rarely exercised real control over defense and foreign policy.

In the US, Democrats and Republicans accuse each other of controlling the ‘deep state.’ Democrats claim the pro-Republican arms lobby and military-industrial complex constitute the deep state, while Republicans argue that Ivy League universities promote ‘wokeism’ and diversity, equity, and inclusion narratives that, according to Donald Trump, undermine America’s greatness. Trump has accused the deep state within the Democratic regime of election interference, citing the Freedom Medal awarded to George Soros as evidence. However, skeptics argue that if the deep state were so powerful, how could Daksh Patel dismantle it simply by firing ‘interns and associates’ whose tenure is co-terminus with that of President Biden? Ultimately, the deep state serves as a convenient scapegoat for anything that goes wrong or for political parties losing popular support.

If Republicans and Democrats are battling it out in Washington, India faces a similar scenario, with Left liberals and Right nationalists accusing each other of leveraging the ‘deep state’ to gain or retain power. Publications like The Caravan and Organiser Weekly lead these respective narratives. Left liberals claim the RSS is India’s deep state, while Right nationalists accuse the Ford Foundation and George Soros’ Open Society Foundations of attempting to discredit the democratically elected Modi government. Left liberals find support in the speeches of Leader of Opposition Rahul Gandhi, while Right nationalists, led by Vice President Dhankhar, minister Kiren Rijiju, and BJP spokespersons like Sambit Patra, vehemently counter these claims.

Who constitutes India’s Deep State?

In a pre-budget article for The Indian Express, economist Surjit Bhalla, a former member of the PM’s Economic Advisory Council, alleged that India’s deep state comprises “major industrialists, senior IAS babus, and their friendly influencers in the media”, slowing down economic growth. This claim was firmly repudiated, point by point, by Vivek Kaul in Newslaundry, who questioned the logic behind such allegations. Kaul argued that neither the IAS, corporates, nor the media benefit from economic deceleration. Instead, he pointed out that the real cause of economic slowdown is the compulsion of all political parties—BJP, Congress, and AAP—to allocate budgetary resources to freebies rather than long-term investments in social and physical infrastructure, which are crucial for sustained economic growth.

Journalist Josy Joseph, in his book The Silent Coup: A History of India’s Deep State, argues that the deep state is actually led by the IPS. He claims that in the name of combating terrorism in Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, and the Northeast, as well as ‘Left-wing extremism’ (LWE) in Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, and Andhra Pradesh, the triumvirate of the NIA, CBI, and ED have consolidated unchecked power, with neither the legislature nor the judiciary exercising adequate oversight. He documents human rights violations of individuals caught in the crosshairs of state action.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Steve Coll offers another perspective, alleging that India’s deep state mainly comprises serving and retired IFS officials. However, if the IAS, IPS, and IFS were truly dominant, why would they have allowed the creation of the Department of Military Affairs under the Chief of Defence Staff, effectively relegating the Defence Secretary (an IAS officer) to a largely ceremonial role?

A completely contrarian view is presented by Sandhya Ravishankar, news editor at NDTV Profit. She argues that global NGOs and foreign funding agencies have attempted to damage India’s international reputation by supporting anti-CAA protests and farmers’ agitations against the farm laws. Quoting the French publication Mediapart, she alleges that the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) received $47 million from the US Deep State to produce investigative reports targeting governments opposed by Washington—a charge firmly denied by the US Embassy in New Delhi.

She lists organisations such as the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (led by Maja Daruwala, daughter of the legendary Sam Manekshaw), the Indian Police Foundation (chaired by celebrated police officer Prakash Singh), the Centre for Policy Research (affiliated with Yamini Aiyar and Pratap Bhanu Mehta), and the National Foundation of India as key actors producing reports that allegedly undermine India’s prestige on the global stage. She describes this phenomenon as the ‘weaponisation of soft power.’

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Until recently, he was director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration.