BRICS grouping expands to a team of eleven

- September 12, 2023

- Posted by: admin

- Category: India

The new members are neither averse to India nor can be seen as only pro-Chinese. Some have good relations with the US and the West.

Gurjit Singh

Former Ambassador

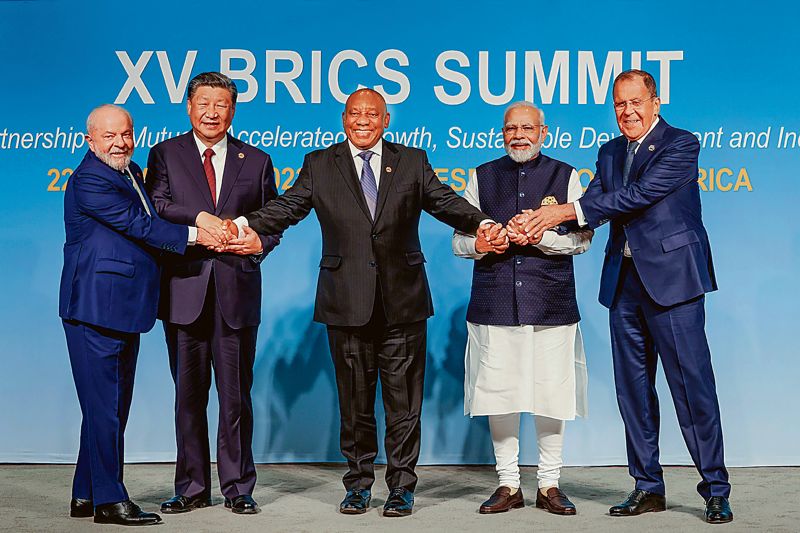

THE 15th BRICS summit, the first in-person edition since the outbreak of the Covid pandemic, was held in Johannesburg, South Africa, earlier this week. Its key outcome was a 94-paragraph communique; deciding to add six members and holding a BRICS-Africa Outreach and BRICS Plus Dialogue encompassing almost half of the Non-Aligned Movement countries were its highlights.

There were some major points of interest regarding this summit. The first was what direction it would take. Would it be more of a Chinese and Russian-backed view of the growing bipolarity and become a part of it, or would it remain a middle-of-the-road alternative? BRICS came into being as emerging economies wanted an alternative to the Bretton Woods system. The financial crisis of 2008 led to the first BRICS summit in 2009 and the inclusion of South Africa in 2010.

Amid the Ukraine crisis, China has challenged the US and made more friends. Hence, the expansion of BRICS is viewed as an opportunity to create a phalanx of countries which would be beholden to China and its economic might, and a challenge the US domination.

The India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) trilateral of 2003 preceded BRICS. It was a three-continent, three-democracy grouping of the Global South. When South Africa was included in BRICS, IBSA more or less got merged with it and has had no separate summit since 2011.

As China and Russia are pushing BRICS towards an anti-US stance, the IBSA could have prevented BRICS from moving in that direction. The IBSA coordination would also have been useful in the context of the G20 presidency, currently held by India and to be taken by Brazil and South Africa (endorsed in the Johannesburg Declaration). However, these hopes were belied because South Africa has largely followed the Chinese lead in pursuing the BRICS goals.

This is a loss for the Global South. South Africa invited 69 countries, including all African nations, to the BRICS summit. They included the 22 countries that had formally requested to join it. Holding such a large, unwieldy event was perhaps an effort by South Africa, backed by China, to indicate that they too — like India — are champions of the Global South.

Besides this approach, the other important aspects were expansion, what shape it would take and the so-called effort towards ‘dedollarisation’. It was widely expected that India and Brazil would resist quick expansion, and instead look for a criteria-based approach. Up to a point in the summit, it appeared that this was the way things would go and other countries would be included in a phased membership process, beginning with BRICS Plus or BRICS partners, which could later graduate to membership. In the early stages of the summit, after much effort, a document on the process and the criteria for expansion was adopted. Within a day of that, six new members were announced. The expectation that there would be some processes undertaken before that was belied. The communique does say that the criteria established now will have the foreign ministers look at new partners, which means that the BRICS expansion is not yet over.

In the later stages of the summit, the China-Russia-South Africa combine pushed through an immediate expansion. India and Brazil were not averse to it and, therefore, seemed ready with who they were to support in case of expansion. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announced meetings prior to the summit included those with the leaders of Iran and Ethiopia, who were admitted as members. The PM also met Filipe Nyusi, President of Mozambique, a major energy partner, and Senegal President Macky Sall, who had approached India for the African Union’s admission to the G20.

Indian support for Argentina, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE was easier as they are all New Delhi’s strategic partners. While the expansion was virtually sudden, the new members admitted are neither averse to India nor can be seen as only pro-Chinese. Some have good relations with the US and the West as well.

The criteria are not yet known. Nigeria and Indonesia, both big countries with emerging economy status, were ignored. Are democracy and economic status not criteria for membership? Sources say that, perhaps, Nigeria and Indonesia were diffident about joining BRICS. Perhaps, it was the strong lobbying by those ultimately admitted that led to them getting ahead in the process.

Regarding ‘dedollarisation’, it seems to be an overrated concept. Despite proclaimed Chinese strength, its economy is not doing well. Russia is under sanctions. South African economy itself is in the doldrums. The original reason for the formation of BRICS was to bring together a group of robust emerging economies, which had slowed down. Countries within BRICS are trading among themselves in their own currencies. Now, more efforts will be made. The Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors will discuss the issue of local currencies, payment instruments and platforms, and report at the next summit in Russia. The New Development Bank (NDB) is also making an effort in that direction but trading in their own currencies without a clear reference currency, or a stated monetary policy, seems far.

The best part of BRICS has been NDB, which is modest but steady. The new members need to contribute to it in equal measure and not be junior partners. Some like the UAE and Saudi Arabia have robust capacities and can be expected to invest. Among the new members, the UAE and Egypt are now in the NDB, as are Bangladesh and Uruguay, but the other new entrants need to join the bank.

The other new members would have some problems since they are eagerly looking for support rather than to contribute. Therefore, the criteria to expand BRICS should have included a minimum threshold of GDP, and the ability to contribute to BRICS and the NDB. After all, BRICS membership should not bring only the right to milk the system, but also to be an important part of a pole in the preferred multipolar order.