At defence PSUs, bring new appraisal system. Job security doesn’t help national security

- August 20, 2023

- Posted by: admin

- Category: India

Identified posts in the DPSUs should also be thrown open to persons who are outside the government and possess the required basic qualifications.

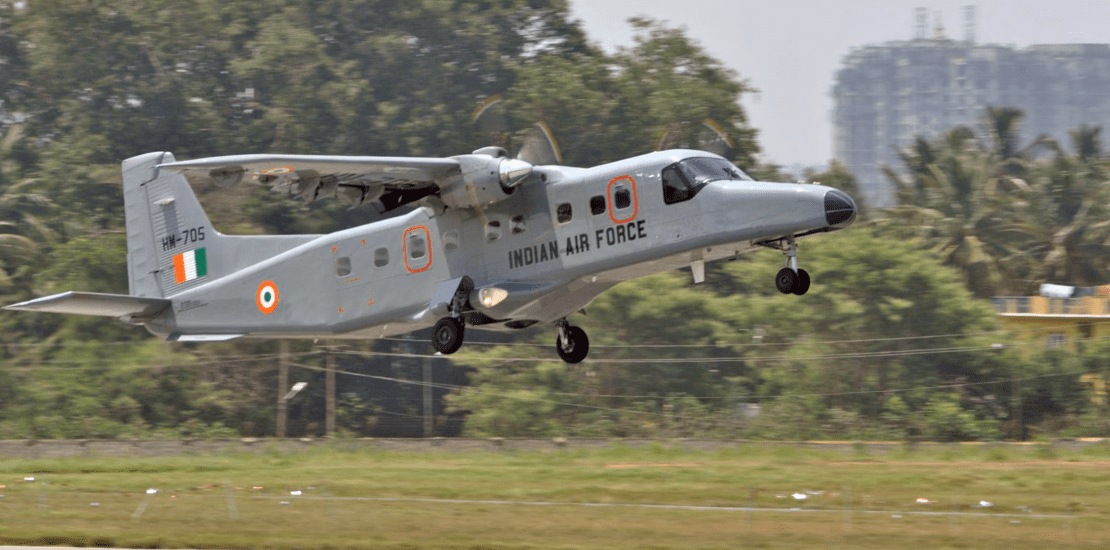

Some of the recently corporatised Defence Public Sector Undertakings such as the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited will be put to test by deals, including the production of the GE F414 jet engine. HAL’s record of productivity and quality assurance is far from encouraging and is perhaps illustrated in an interaction, a friend once told me, between the head of a foreign aircraft manufacturing company and the Chairman of the HAL.

The foreigner was first given an impressive presentation of HAL at its Headquarters in Bengaluru and thereafter taken on a tour of the PSU’s extensive infrastructure facilities situated all over India. On returning to Bengaluru, he was asked by the chairman – ‘What are your impressions’? The foreign head replied – ‘Your infrastructure is extremely impressive; in comparison to yours, ours ’looks like poorly organised workshops. But why don’t you make aircraft?

An earnest attempt to answer that question would result in a blame game among the stakeholders that primarily includes the Government of India, especially the Ministry of Defence, DRDO and the HAL top brass. Policies, financial outlays and failure to leverage human capital would find a prominent place in a long story that has resulted in the failure to produce an indigenous aircraft.

Addressing the human capital problem

In my column last week in ThePrint, the focus was on DRDO and its human capital problem. This time, it is about human capital in the larger public sector. The assumption is that without reform aimed at improving the quality of human capital at all levels in the Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs), it is not possible to achieve the required degree of productivity and quality assurance — a key component of military effectiveness.

The human capital problem in government resides in the human tendency. Long-term security provided by an assured life-long employment morphs into a self-serving venture that undermines organisational needs. Admittedly, there would be some individuals who would not fall in this category but the majority unfortunately does and that is what matters.

Due to the national security implications of the performance of the DPSUs, there is perhaps a case for the government to bring about a reform that to some degree dilutes the assurance of a permanent job by linking it to individual performance. This ought to be followed by opening identified posts in the DPSUs that should also be thrown open to persons who are outside the government and possess the required basic qualifications. This suggestion may sound politically impracticable for any government to undertake, especially in the face of demanding labour unions and recurring elections. Be that as it may, it should not prevent the political leadership from processing the idea and taking it forward wherever/whenever possible. The core argument is strong as long as one admits that there is a human capital problem that urgently needs to be addressed.

The human capital problem is not only confined to the DPSUs, it is a larger malaise that pervades the whole of government. But since national security is involved, it must in particular encompass the Ministry of Defence and all its departments. It is also necessary to start at the top echelons where there is absence of labour union resistance. There is also hardly any point in reforming only the DPSUs without simultaneously including the civil service component in the MoD. But how?

A new system needed

It is well within the powers of the government to identify posts that need to be thrown open instead of retaining them as the preserve of civil service cadres that includes not only the entire Civil Service of the Union but also those of the DPSUs, DRDO etc. Whether or not the selection process would require enlarged capacity for the UPSC, Public Sector Employment Board or any Special Commission under the Management Board of the seven corporatised DPSUs, is a matter of detail that should not be difficult to manage.

Once the best man is picked for a post, he must be given at least a three-year tenure. For persons who are from outside the government, the tenure could be based on a contract system. Such a selection system being confined to identified posts could be restricted to the officer grade level.

For personnel below the officer grade, a different system would have to be followed. The new system could borrow its conceptual moorings from the Agnipath system that has been introduced for the Armed Forces. The conceptual basis of the Agnipath Scheme is founded on the notion that job security is related to performance. In the case of the DPSUs, which includes 41 factories, the initial recruitment should be based on a four-year tenure and only about 25 per cent-40 per cent should be absorbed permanently. There would also be a need to modernise/upgrade the machines in the factories to improve productivity and quality. This would also help reduce the workforce.

There is definite need to explore the legal possibility of terminating the services of personnel who do not meet the minimum expected standards. Presently, the legal framework does not easily permit the termination of services from a government job. There is no doubt that such measures are urgently called for. The existing provisions for protection of the rights of individuals through labour laws should not be allowed to act as a shield for protection for those shirking on their responsibilities or found to be incompetent. This matter is definitely complicated but it is time that the government reviews this issue in a comprehensive manner for the whole of government.

National security is heavily reliant on the DPSUs, underlining the importance of its human capital. Currently, productivity levels are low within this unionised workforce and need to be bolstered. Boosting productivity requires a shift away from viewing these roles as untouchable government jobs.

Complacency is natural when job stability is not a concern but it gravely hinders India’s transition — from being one of the largest arms importers towards becoming able developers of indigenous capabilities. This transformation calls for a change in the prevailing mindset.

It has become truly necessary to rewrite the existing rules for government sector jobs so that individuals at all levels are regularly evaluated and positions remain open to external candidates who may be better suited for their roles. The introduction of concepts like the Agni Path of the Indian Armed Forces, with modifications, in the government segments of the defence industrial base should definitely strengthen India’s efforts for achieving self-reliance while providing the armed forces with state-of-the-art military instruments.

Lt Gen (Dr) Prakash Menon (retd) is Director, Strategic Studies Programme, Takshashila Institution; former military adviser, National Security Council Secretariat. He tweets @prakashmenon51. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)