Syed Ata Hasnain | Global shift? China is on a geopolitical overdrive

- April 17, 2023

- Posted by: admin

- Category: China

By: Syed Ata Hasnain

Syed Ata Hasnain, a retired lieutenant-general, is a former commander of the Srinagar-based 15 Corps. He is also associated with the Vivekananda International Foundation and the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.

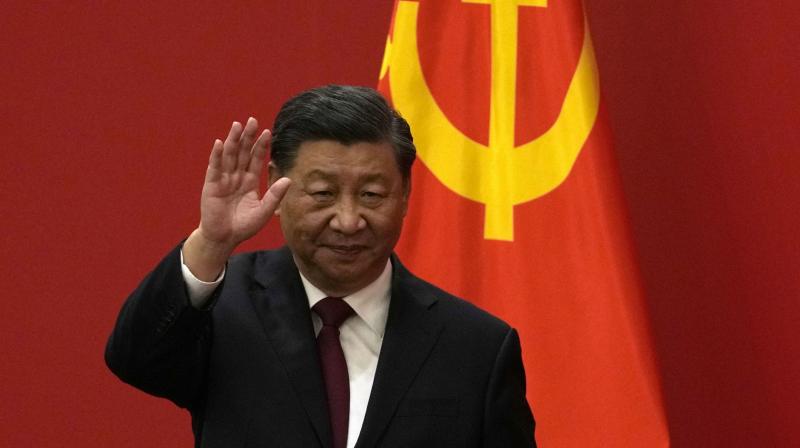

With the Russia-Ukraine war going past its one-year mark and showing little sign of abating anytime soon, the world is learning to adjust itself to the effects of the war. Among those quick to respond is China. In two areas we have seen the Chinese footprint enhance through recent events. First was the visit of President Xi Jinping to Moscow and the endorsement he handed out to President Vladmir Putin over his policies. The second was the surprising announcement of a China-sponsored Iran-Saudi Arabian accord signalling Beijing’s first serious foray into Middle East geopolitics; Xi Jinping had visited Saudi Arabia in December 2022 to attend the first China-GCC summit.

Two reasons appear to stand out for China’s proactiveness. First, the Chinese strategic outreach expected from the Belt and Road Initiative has perhaps not delivered to the level expected. Second, Mr Xi’s personal ambition of getting things on the move to achieve the objectives he has laid out for 2035 is spurring things in foreign policy. The war in Eastern Europe has worked to China’s advantage more than against it. It has helped to force American attention and focus to that region with full commitment, thus staving off the inevitable attention that the US would bring to the Indo-Pacific. An increase in Chinese geopolitical activity and presence in the Middle East has been evident for some time. China’s economic growth is dependent upon guaranteed energy supplies for its manufacturing sector. Part of that comes from Russia and Central Asia, but the majority reaches China’s eastern seaboard from the Middle East. It is the biggest purchaser of energy from Iran and Saudi Arabia, contributing hugely to those economies, which have also been under stress and strain. A guaranteed supply source is what China desires most, along with secure supply routes for its manufactured goods.

Interestingly, China has also set out a framework for a political settlement to the conflict in Ukraine. Probably hit by the international hype given to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s sage advice to President Vladimir Putin at a meeting on the SCO summit’s sidelines in August 2022, China was smarting. Xi Jinping does not wish to be seen as only an instigator and supporter of war through the backing given to Mr Putin and Russia but his peace plan is below par and a disappointment for those expecting a roadmap to peace. The proposal lacked specifics about contentious issues like resolving the various territorial disputes between Kyiv and Moscow or providing any security guarantees for Ukraine. A plan devoid of any proposed or eventual withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory is a non-starter. However, a maximalist approach should be expected in any plan with progressive compromises; that is how all genuine peace proposals work. It does appear that China was taken by surprise by the start of the Ukraine war, despite the famous “no limits friendship” statement by Chinese and Russian officials during the Beijing Winter Olympics in early February 2022. Beijing has not supported Russia in the UN and has not provided Russia with weapons; it has publicly proclaimed neutrality. It has, however, supported the Kremlin’s basic issues about the war, seriously opposed sanctions against Russia and has helped with energy purchases to support the Russian economy, which otherwise cannot sustain the war. It needs Russia for some sophisticated weaponry (S-400, Su-35). A Russian military defeat, leading to Mr Putin’s downfall would be a nightmare scenario for it. A beholden Mr Putin, with Russia a virtually junior partner, an image of China as a virtual geopolitical pole and the US’ Indo-Pacific strategy on temporary hold, all works to the advantage of China.

Now the Middle East. As already stated, energy guarantees are important for China but more than that is the necessity of creating the image of a geopolitical referee in the region. Beijing’s foreign policy of balancing between rivals and increasing multilateralism has enabled it to deepen its ties with the Middle East, although jumping straight into an old and contentious conflict such as the Iran-Saudi one is bound to have its own complications. The outreach to Iran through the 25-year $400 billion strategic and economic deal cut in 2021 is not something unexpected, with Iran pushed to the wall by the US. It’s the taking of Saudi Arabia on board which is a potential coup, as it upsets a long-lasting US-Saudi relationship and throws the future strategic equations of the Middle East into disarray. China is now involved in Grand Mosque revamp projects in Saudi Arabia and remains the largest investor in Egypt’s Suez Canal Area Development Project, which is Beijing’s most important shipping route to Europe. While the Iran-Saudi deal may be strewn with challenges, China’s entry as a serious player in the Middle East is bound to cause concern for the US. Israel, in whom the US has invested so much, may also not be too happy with the interplay with Iran and Saudi Arabia.

What is for India in all this renewed Chinese geopolitical vigour. First, Russia could sooner than later become completely subservient to China. There could then be erosion in the remnants of the Indo-Russian relationship contingent upon how hard the United States and the West works on incorporating India into their future Indo-Pacific strategies. The Indo-US strategic partnership and India’s membership of the Quad exist with full transparency, but the degree of commitment by India under the current circumstances remains a challenge. Its membership of multilateral equations and groups on both sides of the divide in the current Cold War puts it in a crucible, where all kinds of pressures will be applied. The Russia-China combine will definitely not be strategically happy to push India firmly into the US and Western groupings; India’s grey zone commitment thus far may be suitable as it places it virtually in the realm of being a swing power. However, in the future this is going to be a serious challenge, especially as material aspects of the Indo-Russian relationship start drying up; the non-arrival of the remaining contracted S-400 systems may just be the tip of the iceberg. Even with the very sensible “Atma Nirbharta” policy in place, it will be some time before India could be self-sufficient in advanced military equipment. The moment we tilt our scale a wee bit more towards the US and the West, the tenuous balance so adroitly played out by the Indian government so far is likely to be upset. That needs a separate analysis to imagine its impact on the ground.