Military expansion among ASEAN members

- September 12, 2023

- Posted by: admin

- Category: ASEAN & ARF

The changing world order and the growing Chinese aggression in the SCS have compelled the ASEAN countries to increase their military expenditures

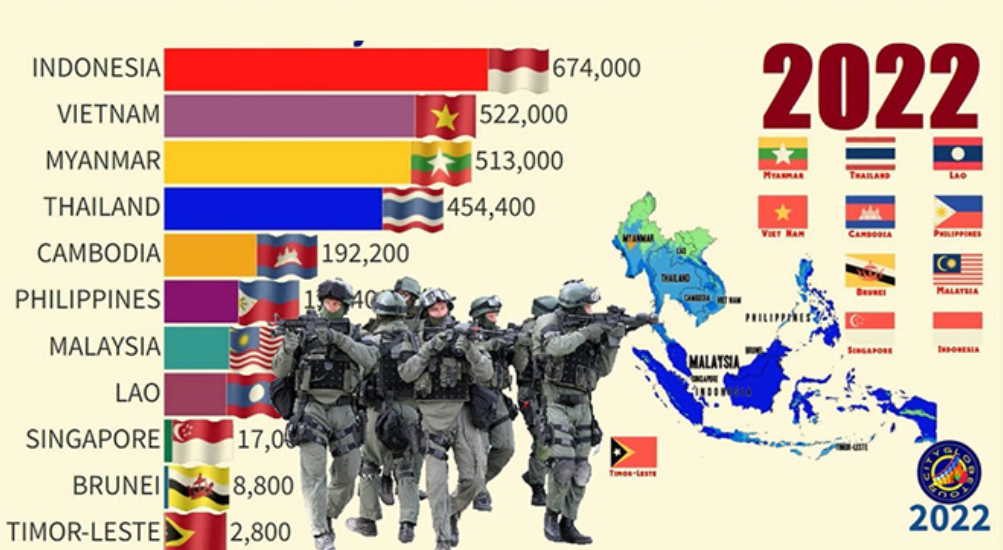

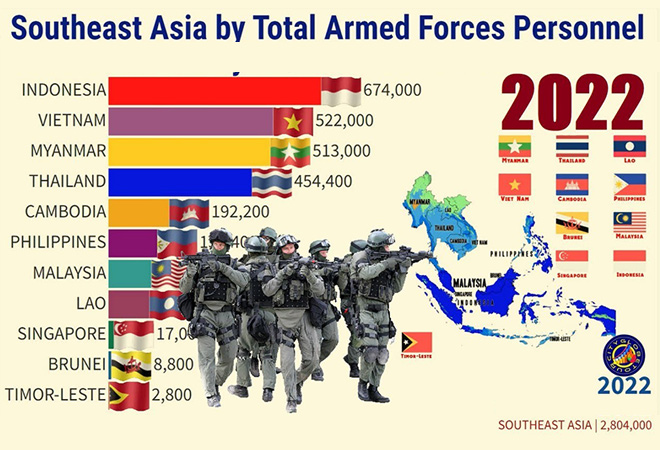

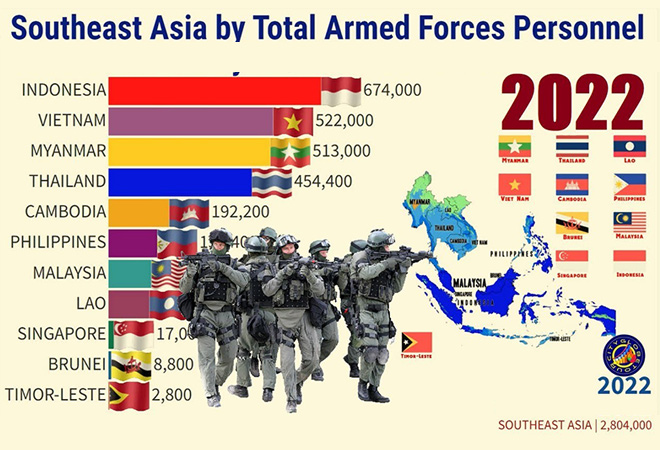

Source: CityGlobeTour/YouTube

- ASEAN MEMBERS

- CHINESE AGGRESSION

- DEFENCE SPENDING

- MARITIME SECURITY

- MILITARY EXPANSION

- REGIONAL DYNAMICS

- THREAT PERCEPTIONS

With global dynamics changing due to big power rivalry, the Indo-Pacific region is challenging the traditional concept of the Asia-Pacific with ASEAN at its core. Several ASEAN-centric bodies provided the regional security architecture. The United States (US) and its Quad partners—India, Japan, and Australia—have decided to challenge China’s aggressive intent in the South China Sea (SCS) and in the larger Indo- Pacific. ASEAN worries that it may have to choose sides.

ASEAN integration with the Chinese economy is intense. Its defence engagement with China is constrained by China’s assertiveness in the SCS and claims over its ‘traditional rights’ as outlined by the nine-dash line. This brings it into conflict with five ASEAN countries, notably Vietnam and the Philippines; the contention with Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia is more muted.

The Quad, the AUKUS, the threat of a Taiwan conflict, and the Ukraine crisis cause anxiety to ASEAN. ASEAN’s traditional posture of a liberal construct to deal with security challenges is failing. The Chinese have upended the reality in the SCS while providing lip service to ASEAN’s efforts to have a Code of Conduct (CoC) since 2002.

There is enhanced threat perception and defence spending by ASEAN countries. It cannot be termed as an arms race because ASEAN members are generally not competing with each other, nor are they in a position to challenge China or other inimical powers. Yet, military acquisition is increasing as maritime security moves centre stage.

The Chinese have upended the reality in the SCS while providing lip service to ASEAN’s efforts to have a Code of Conduct (CoC) since 2002.

ASEAN countries have a modernisation process underway. This has several aspects to it. Some started a while ago, but the need to bolster defences and replace equipment has had a link to Chinese aggression since 2010. According to the SIPRI Military Expenditure database 2023, ASEAN’s military expenditure increased from US$20.3 billion in 2000 to US$43.2 billion in 2021. From 2002-2007, this was below US$30 billion annually. Since 2015, ASEAN countries spent US$41 billion or more, the highest being US$ 44.3 billion in 2020.

From 2012, Chinese aggression in the SCS grew, cleaving ASEAN and bringing Chinese ships to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), waters and shoals of five ASEAN countries. Notably, military expenditure increases began in 2013, when expenditures leapt from US $34 billion to US $38 billion and have been growing since. Among ASEAN countries, according to SIPRI, from 2002-2021, Singapore has had the largest defence budget, reaching US$11 billion. The next was Indonesia with US$8.2 billion in 2023 marginally lower than US$ 9.3 billion as seen in 2020. Since 2012, Indonesia increased its defence expenditure from US$ 6.5 billion to US$ 8.3 billion in 2013 and has maintained a steady level.

Thailand is another major importer of weaponry with a budget of US$ 6.6 billion though it had maintained US$7 billion per annum for the previous three years. Malaysia and the Philippines both crossed the threshold of US$3 billion per annum and maintained it for a decade. These are likely to rise.

SIPRI does not have reliable defence expenditure figures for Vietnam but places them around US$ 5.5 billion per annum. Vietnam ceased publishing its defence budget in 2018 when it was estimated at 2.36 percent of its GDP. In December 2022, Vietnam held its first Def Expo; 170 exhibitors from 30 countries participated, which is a sign that Vietnam, facing Chinese hostility consistently, aims to diversify its Russian defence base. JSC Rosoboronexport (Russia), Lockheed Martin (US), Airbus (Europe), BrahMos Aerospace (India) and Mitsubishi Electric (Japan) had participated. Chinese companies, though invited, were absent. Vietnam relied on Russia for 70 percent of its weaponry. Most of its large equipment is Russian. The dependence decreased to below 60 percent in 2021. The US lifted an embargo on weapon transfers to Vietnam in 2016. Since 2017, the US and South Korea became suppliers.

Chinese aggression in the SCS grew, cleaving ASEAN and bringing Chinese ships to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), waters and shoals of five ASEAN countries.

South Korea has enhanced its exports to ASEAN. Korean Aerospace Industries in February 2023 signed a US$910-million contract for 18 FA-50 fighters to Malaysia; they challenged the offer of India’s Tejas aircraft. While Malaysia is not among the major arms spenders, its engagement with South Korea and Türkiye is growing. According to SIPRI, between 2017 and 2021, South Korea sold over US $2 billion of defence equipment to the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Malaysia.

Threat perceptions and its implications

The perceptions of threats among ASEAN member states and how they should confront them varies. Some are more comfortable in dealing with the US, Australia, and Japan who are Quad members; others are more circumspect. The difference is due to the threat perceptions. Vietnam and the Philippines, for instance, are the biggest victims of Chinese aggression in the SCS. China has occupied islands and challenged control by Vietnam and the Philippines over islets and shoals that were traditionally governed but not defended. The Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal with the Philippines and Johnson Reef with Vietnam have witnessed such aggression. Therefore, the expansion of Vietnamese and the Filipinos armed forces and equipment and capabilities are an important factor.

In cases where military coups have occurred, such as in Thailand and Myanmar, the expansion of the armed forces was faster and more sustained. Some equipment purchased by Myanmar and Thailand cannot be easily linked to direct threats because these countries are not engaged in direct confrontation with China in the SCS. They have no ostensible enemies except within; yet obtaining submarines like Thailand received from China in 2017 and Myanmar obtained from India as a gift looks odd. Myanmar is perhaps responding more to Bangladesh acquiring Chinese submarines. Submarine acquisitions by Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia are also noted in ASEAN.

China has occupied islands and challenged control by Vietnam and the Philippines over islets and shoals that were traditionally governed but not defended.

In several ASEAN countries, the ideology behind the defence of the realm has altered. While the control by the military in Thailand and Myanmar gives impetus to defence expenditure there, in Indonesia and the Philippines, the move away from military governments towards democracy goes in the other direction. Instead of large armies, intended for internal control, and dealing with counter-insurgencies, the emphasis shifts to understanding the maritime challenges and acquiring naval and air assets for developing maritime security capabilities.

In democratic societies, budgetary constraints often come in the way of purchasing new equipment. This requires the executive to coordinate with the legislature and the Treasury. This impacts the kind of weapon systems that are being acquired or have become lost opportunities. The ability to coordinate these internally led the Philippines to outrun Indonesia and Vietnam in ordering the BrahMos missiles from India. In Indonesia, the order has not materialised, because internal coordination between the government and Parliament is inconclusive.

It is not entirely clear why Vietnam, despite its interest in the Brahmos and placing orders for weapons from other sources, is hesitant, though it happily accepts a gift of a warship from India.

In the case of Indonesia, they ordered 42 Rafaeles from France. Meanwhile, they obtained 12 second-hand Mirage 2000-5 fighter jets from Qatar for US$792 million. This is the impact of budgetary constraints.

The Philippines during the first Horizon (2013 to 2017) purchased military hardware for internal security. The second horizon (2017 to 2022) focused shifting from internal security to territorial defence. The Philippines allocated US$ 5.6 billion for Horizon 2 and US$ 4 billion for Horizon 3 (2022-2027).

The ability to coordinate these internally led the Philippines to outrun Indonesia and Vietnam in ordering the BrahMos missiles from India.

Thailand, in 2022, ordered armed reconnaissance AH-6 helicopters from the US and Hermes 900 drones from Israel to support maritime operations. Singapore’s 2023 defence budget is US$13.4 billion, witnessing a 10-percent increase over 2022. It will include buying 8 (STOVL)-capable Lockheed Martin F-35B fighter aircraft to replace its F16s. Malaysia, besides the Korean fighters, will acquire three unmanned aerial systems from Turkish Aerospace Industries, and two maritime patrol aircraft from Italian firm Leonardo. In Indonesia, new helicopters, aircraft, naval vessels and surface combatants, military rotorcraft, submarines, underwater and electronic warfare systems, are the key components for expansion,

SIPRI indicates that in 2021, ASEAN countries spent US$43 billion on defence, merely 2 percent of worldwide defence expenditures. Comparatively, the US spent US$ 827 billion (39 percent), Europe US $418 billion (20 percent). China spent US$ 292 billion (13 percent) and Japan and South Korea both spent US$ 46 billion (2.1 percent) each.

The surge started around 2010. Russia was quick to provide equipment particularly Sukhoi aircraft to Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Submarines were also popular. The Ukraine crisis and US nudging led ASEAN to avoid Russian equipment. Between 2000 and 2020, Russia was the largest arms supplier to ASEAN with sales of US$11 billion compared to US$8.4 billion from the US. The cost factor, the non-interference by Russia in the internal matters of ASEAN countries, and sometimes the use of barter arrangements by payment in commodities helped Russia. The US sanctions on Russia reportedly led to the cancellation by Indonesia of the Sukhoi 35 fighter deal and reduced the Philippines’ interest in buying 16 military helicopters.

Due to the Ukraine war, Russia is constrained in supplying weaponry. Its diminished capacity leads ASEAN to buy new equipment from American, European, and other Asian countries. The biggest advantage is for South Korea. They provide good technology at competitive cost, with little interest in the domestic politics of ASEAN. Given the new impetus to military modernisation in ASEAN, the market serves a good opportunity for middle powers to expand their imprint especially India.

Gurjit Singh is India’s former ambassador to Germany, Indonesia, Ethiopia, ASEAN and the African Union.