1965 – No Victor no Vanquished?

- September 5, 2023

- Posted by: admin

- Category: Pakistan

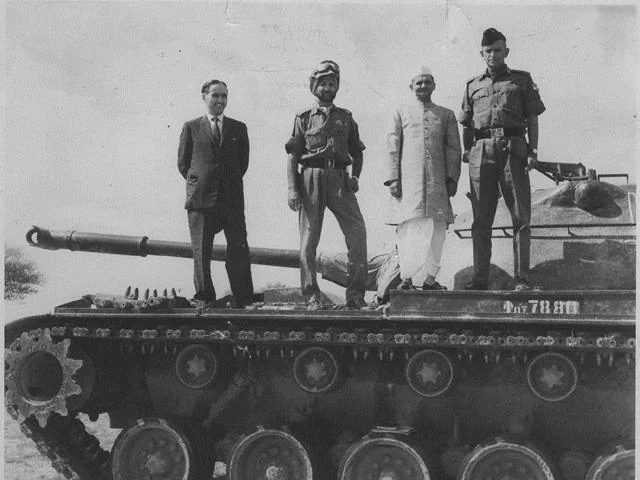

The 1965 India – Pakistan war was brought to an end on 22nd September 1965 by a ceasefire brokered by the United Nations. The situation on ground as on that day in various sectors was such that India had a markedly upper hand. In Jammu and Kashmir, the Pakistani raiders launched through the Line of Control across the entire state under their Operation Gibraltar had been stopped, killed, captured or beaten back . The strategically important Hajipir Bulge had been captured by India. Pakistani armoured offensive under ‘Operation Grand Slam‘ in the Aknoor sector had been beaten back. The Indian 1 Armoured Division had broken through the initial lines of Pakistani defences and was poised inside Pakistani territory, ready to threaten Sialkot. The Indian offensive in Punjab, in the Amtrisar – Lahore sector, was progressing well, with a foothold having been established on the Icchogil Canal. The Pakistani counter-offensive in Punjab, in the Khem Karan Sector, had been blunted and beaten back. Scores of Pakistani battle tanks scattered around Khem Karan and Asal Uttar – some destroyed and others abandoned in perfect working condition – bore testimony to the total rout of Pakistani Armoured Division leading this thrust. Under these circumstances, the ceasefire came as a welcome face saving exit for Pakistani government and Army – which were virtually the same thing.

Subsequently, under the Tashkent Agreement of 10th January 1966, signed between PM Lal Bahadur Shastri and President Ayub Khan, both forces gave up the territorial gains and status quo ante was ensured. Under the Agreement, the countries agreed –

The death of PM Shastri the same night, hours after signing the Tashkent Agreement, is still shrouded under a veil of myriad unanswered questions. President Ayub continued as a lame duck head of state for another few years before he was finally forced to resign in 1969. For India, the outcome, though not an outright victory, did come as a redeeming factor after the ignominious defeat by China in 1962. The Pakistani side, typically, continued to claim it as a thumping victory, and their populace is still under this misplaced belief that unlike 1971, 1965 war was won by them. Indian commentators have been more realistic in accepting the outcome as a stalemate.

Looking back at the events from the vantage point of half a century later, and the added luxury of a dispassionate perspective via the lens of de-classified CIA documents, some questions remain unanswered. Here are extracts of the relevant CIA Intelligence Memorandum with some key highlights that emerge from underlined text.

Analysis of the document and subsequent events indicate that –

- The hostilities were initiated by Pakistan who infiltrated guerrillas led by regular army personnel into Kashmir, and due to any Indian aggression as long claimed by Pakistan.

- The end was indecisive, due to a ceasefire which both sides were reluctant to agree to.

- India had made substantial gains in the Lahore and Sialkot sectors besides having captured the strategic Hajipir bulge in Jammu and Kashmir.

- Pakistan had ‘contained’ the Indian forces, but were unable to ‘bring them to their knees’. This means that Indian forces had been temporarily halted. They had made substantial territorial gains as above, and if they had even continued to hang on to their ‘contained’ positions, Pakistan couldn’t muster the strength to evict them.

- The military cost to Pakistan was substantially higher.

- Pakistani public had been led to believe by government propaganda that they were winning the war. An end to the war without any gains in Kashmir was therefore difficult for their leadership to sell to their people.

- Bhutto even threatened to pull out of the UN if the Kashmir issue was not resolved.

- India’s firm refusal to discuss Kashmir led to his bluff being called.

- Under these circumstances, Ayub was considerably weakened, and the document predicts (quite accurately, as subsequent events proved) the threat of secessionism in East Pakistan (Now Bangladesh).

- Shastri, on the other hand, had emerged much stronger. Having taken over as Prime Minister after the death of and under the long shadow of Nehru, he would no longer be considered as an insignificant entity after a decisive victory over Pakistan.

All of above indicates that if the ceasefire had not been imposed, India was on the trajectory to a clear victory akin to the one it finally achieved in 1971. Therefore, India’s acceptance of the ceasefire, subsequent concessions at Tashkent and the mysterious death of PM Shastri hours after signing the Agreement remain a mystery unexplained to date. Some of the questions that remained unanswered are –

- What prevented India from pressing home its advantage on the battlefield, or even from bargaining hard at Tashkent to gain some advantages rather than settle for status quo ante?

- Would an assertive India under a strong leader (as Shastri had proved himself to be) without having to look over it’s shoulders towards a weakened Pakistan be inconvenient to the global power equations as envisaged by the superpowers?

- India’s inability to convert the decisive military victory in 1971 into significant political gains begs similar questions.

Who were these vested interests that brought about these outcomes? More importantly, now that India is asserting itself economically, diplomatically and militarily once again, and Pakistan is virtually heading towards a failed state status, would such vested interests not be threatened again? Won’t they use every trick in and outside the book to limit and contain India? Are we seeing signs of this around us, in other forms, in the run up to the 2024 elections? Who are these interests and what is their reach?

Paranoid fancies or viable conjectures – left to your judgement.This entry was posted in Military, Military History, Uncategorized and tagged army, Geopolitics, Government, Indian Army, Indo Pak War, Pakistan. Bookmark the permalink.← Uniformly Crazy