G7 and the Chinese conundrum

- July 3, 2023

- Posted by: admin

- Categories: China, Japan

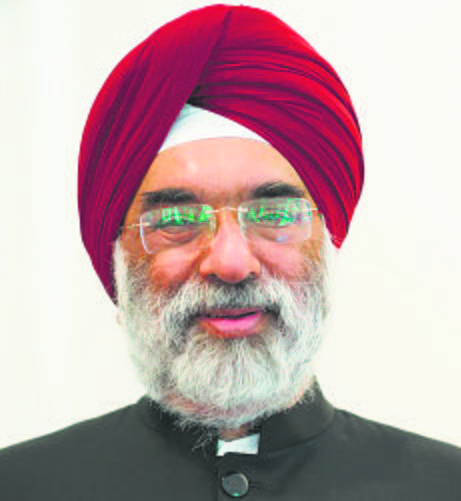

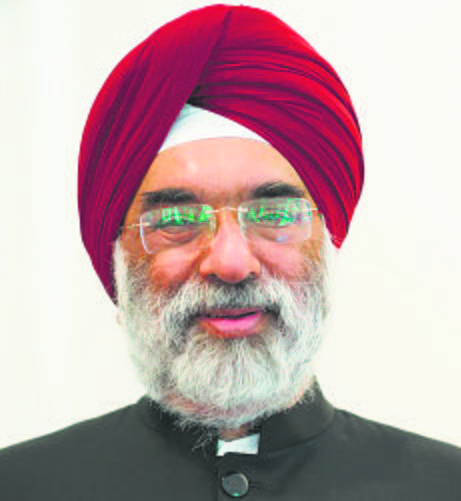

Gurjit Singh

Former Ambassador

THE symbolism of holding the G7 Summit in Hiroshima was not lost on anyone. The city was devastated by an atom bomb during World War II. Last week, the victors and the vanquished of that war stood together in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. The message was to deter Russia from using tactical nuclear weapons in the Ukraine war. “We will starve Russia of G7 technology, industrial equipment and services that support its war machine,” the G7 said. However, it seemed that the platform was used mainly to criticise Russia, not so much to push for nuclear disarmament.

Related News

- Ukraine’s counteroffensive is turning the tide

- Amid Doklam row, India needs to focus on Siliguri corridor

Japan’s focus on the Global South during the Hiroshima G7 Summit was in line with India’s stand as the G20 president.

The G7 remains overwhelmingly bogged down by the Ukraine crisis. Japan’s invitation to Ukrainian President Zelenskyy put the spotlight on Ukraine. Zelenskyy’s unending demands for Western military support contrasted with his appeal for peace. The way the war has progressed shows that his demands will remain on the agenda for a while.

The G7 is united against Russia and is increasing sanctions, whose efficacy remains in doubt. The members’ unity is uncertain when it comes to China. China-related issues such as economic bullying and resilient supply chains were addressed in a generic manner without naming China. “We recognise that economic resilience requires de-risking and diversifying,” a G7 statement said. “We will take steps, individually and collectively, to invest in our own economic vibrancy. We will reduce excessive dependencies in our critical supply chains.”

China was not named because the G7 countries have varying concerns. Japan is worried about the East China Sea and Taiwan; Australia and Canada about trade bullying; Germany and France want a way to continue to deal with China. Consensus on Russia does not easily translate into consensus on China.

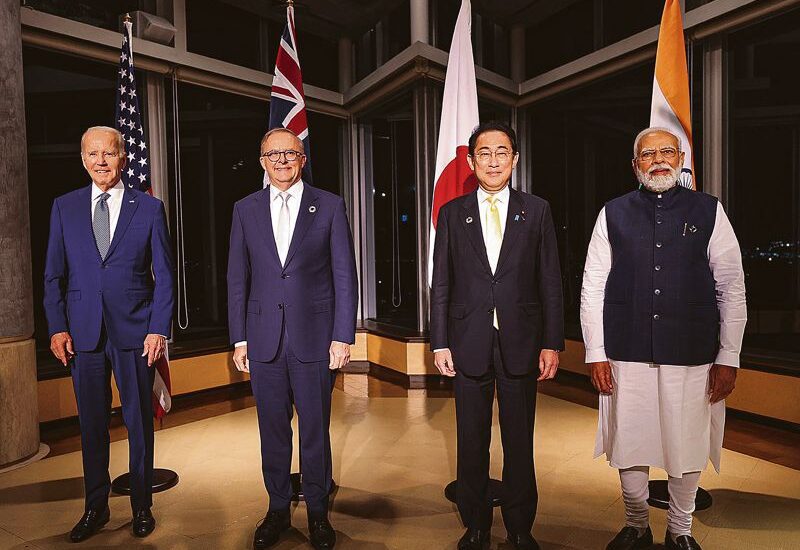

Which of the G7 countries would be the first to engage with China more purposefully? This is a race which is about to start, given the economic downturn in these nations. Quad, comprising the US, Japan, India and Australia, was more eager in seeking peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific maritime domain, but again without naming China.

Japan’s focus was on the Global South too, which was in line with India’s stand as the G20 president. However, Japan is unable to push the G7 towards constructive efforts under the Build Back Better framework. US companies joined the discussion on Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), a collaborative effort by the Group of Seven to fund infrastructure projects in developing nations. It borrows more from the Quad agenda to bring the G7 to collaborate with the Global South. It could have better borrowed from India’s template on how to deal with the Global South.

Among the countries invited by Japan for outreach with the G7 were India, Indonesia, Comoros and Cook Islands as ‘institutional leaders’, besides G7 partners Brazil, South Korea, Vietnam and Australia.

India is now a regular participant in the G7. It is hard to believe that Japan would not have invited India even if the latter had not been the G20 president. This shows India’s rising stature in the international arena.

PM Modi’s participation in outreach events, dealing with functional issues such as food security, health and stable supply chains, was constructive. His 10-point agenda was focused. His presence provided an opportunity for G20-G7 consultations. Japanese PM Fumio Kishida had visited New Delhi and invited Modi for the G7 Summit. They shared the view that it is important for a broad range of partners to work together to address the challenges facing the international community; they also agreed to work together for peace and a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’. Indian advocacy of dialogue and diplomacy to resolve disputes and prioritise the well-being of people is now an accepted template for global engagement.

The PM’s visit to Japan became more productive because the leaders of the Quad nations were able to meet on the sidelines of the G7 Summit. The Quad Summit, which was scheduled for May 24 in Sydney, had been cancelled after US President Joe Biden decided not to visit Australia because of his preoccupation with domestic issues.

G7 summits have mostly revolved around economic concerns, be it the global financial crisis, the Eurozone crisis or the crisis precipitated by developments in the Balkans. The Hiroshima event had all these elements, besides Japan’s domestic issues. It is unusual to have debt ceiling, sanctions, the Russia-Ukraine war, China and Indo-Pacific all fusing into the agenda of a single summit. For all this, multi-pronged solutions are required. Can the G7 do it by itself or does it need to rely on its partners?

The G7 Clean Energy Economy Action Plan, for instance, says that the member nations will work together to frame trade policies that decarbonise their economies, accelerate the development of resilient clean energy supply chains, build common markets for green energy services and generate much more public and private sector investments in climate and energy transition for their partners in the Global South.

In this endeavour, the G7 has been making slow progress. At the Hiroshima meeting, the nations affirmed their commitment to identify new opportunities to scale up the PGII, promising large mobilisation of financing for the requirements of the Global South. Companies from Japan and the US joined to start serious discussions on unlocking public and private capital for quality global infrastructure and investment. The expectations are to raise $20 billion over the next decade. The reality is that hardly $4 billion has been committed. Though the approaches are right, how they will challenge China’s march in the Global South, particularly in the Indo-Pacific, remains unclear.